Building Instruments In Appalachia Gives Those Fighting Addiction A Second Chance

A Beautiful Place With An Ugly Plight

A small sign reading “Dulcimers Made Here” leads into the Appalachian School of Luthiery in downtown Hindman, Kentucky, a small American town huddled in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky. The smell of toasted sawdust intermingles with a faint Appalachian tune wafting in gently from an unseen room. A handful of bearded men sit around various lightly coloured skeletons of guitars, banjos, mandolins, and dulcimers musing over how to start their day.

Hindman is buried in the heart of Knott County, in Kentucky’s historic coal country. Not far from the famous Harlan County, USA, Hindman is a place whose struggling economic reputation is only surpassed by its deep and profound cultural contributions to American music. This is a place where distance is measured by ‘as the crow flies,’ where moonshine is still made deep in family hollers, and where you can still catch the old timers dancing flatfoot style to rollicking oldtime music at community center gatherings every week.

Hindman is a place wholly unique and deeply American with what has become an all too American problem.

I think getting in trouble was the best thing that ever happened to me because it got me to the Luthiery.

Nathan Smith

Troublesome Creek, which runs through the heart of Hindman, metaphorically reflects the disquiet that has become a familiar narrative of Eastern Kentucky, Appalachia, to the rest of America. Knott County’s poverty rate of 32.6% and median household income of $30,503 is a product of big coal’s swift withdrawal from the region after the area’s resources were dug and blasted out of the land, leaving only scarred mountain tops, rusty colored streams, and a community of people waiting in vain for King Coal to return and provide the care they’d become accustomed to.

Nathan Smith, a large man with a dark beard running over his mouth and chin and a voice that sounds like coal rocks on a conveyer belt, worked in the mines for 7 years, but as the jobs dried up he found himself without direction or a steady income. “I had been laid off from the coal mines and I got hooked on drugs really bad after that.” He explains “I was going down a path that would have either laid me in prison or dead. I think getting in trouble was the best thing that ever happened to me because it got me to the Luthiery.”

Hindman School of Luthiery is giving Eastern Kentucky, and its people in recovery, a second chance.

A Seed Sown

Doug Naselroad is a Master Luthier and Lead Instructor at the Appalachian School of Luthiery. A Winchester, Kentucky native, Naselroad was selected as the Appalachian Artisan Center’s Master Artist in woodworking in 2013. Shortly thereafter, he founded the Appalachian School of Luthiery.

It all started a few years ago when a man came into the School of Luthiery begging to be part of their apprenticeship program. “I really didn’t understand why at first, because he was local and I thought, ‘You know you can just come over and sign up,’” recalls Naselroad, “It turned out he had a black mark on his record in the form of a drug related felony and he wouldn’t be able to participate in our apprenticeship program based on our rules at the time”

Little did Naselroad and his colleagues at the Appalachian Artisan Center realize, but the seeds of something new in Hindman were being sown.

“It turned out he was still in full blown addiction and he had plans to go into detox and rehab and he wanted to set a goal that he could work towards as part of his successful recovery. Making a guitar was going to be his reward for getting through rehab.” Naselroad explains, “I think he understood something about the recovery process that we had yet to discover. You have to have a goal to work toward.” Once the man joined the program, he ended up making dozens of instruments and eventually went back to college and got his Masters degree. He now works at a recovery facility about an hour from Hindman. “That experience had been very positive early on and informed our decision to ask ArtPlace America for funding for our Culture of Recovery Project,” Naselroad says.

I think he understood something about the recovery process that we had yet to discover. You have to have a goal to work toward.

Eastern Kentucky has been utterly ravaged by not only by opioid addiction, but meth addiction as well. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, there were 1,160 reported opioid-involved deaths in Kentucky in 2017, at a rate of 27.9 deaths per 100,000 persons, which is nearly double that of the average national rate of 14.6 deaths per 100,000 persons. In Knott County, with a population of 15,291, there were 27 drug overdose deaths between 2012 and 2016 according to the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy.

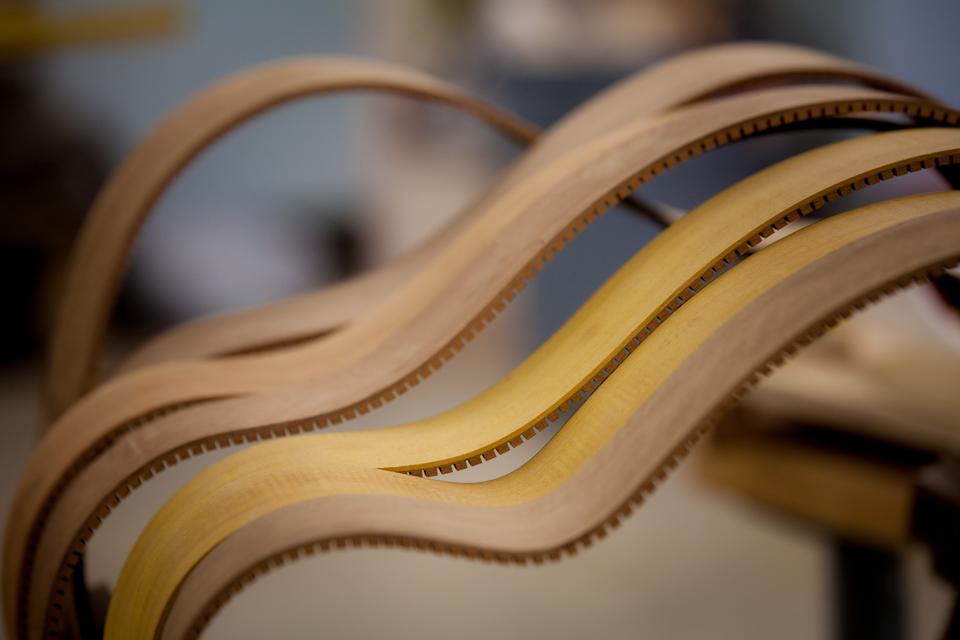

“A lot of bad choices ended me up in rehab,” says Jeremy Haney, a wide eyed, earnest young man working behind a tall contraption barred top to bottom with bent strands of wood pressing against a guitar frame below. When he was young, Haney was prescribed pain medication for a childhood medical condition. He eventually became dependent on the medications, and when doctors around the state stopped prescribing opioids he resorted to taking methamphetamine. “I had been prescribed and taken narcotics for 20 years and once those were gone I was on meth for another seven,” he says.

Before there was the opioid epidemic in eastern Kentucky, there was the methamphetamine epidemic and while the opioid epidemic has taken up a great deal of political and social real estate in Eastern Kentucky drug policy, meth still continues to be an issue in the region. According to an Obama era report, as the opioid epidemic began to gain steam, Kentucky became one of the top ten states where persons age 12-17 were taking pain relievers for non-medical uses between 2009 and 2010. The number of meth lab seizure incidents in the state of Kentucky increased 296%, from 441 incidents in 2008 to 1,747 incidents in 2011. Eastern Kentucky and Appalachia gained a reputation for meth use, as well as being at the epicenter of America’s first chapter in the ongoing opioid saga, the Oxycontin Express, which ran between Central Appalachia and Florida in the early 2000’s.

I had been prescribed and taken narcotics for 20 years and once those were gone I was on meth for another seven.

But as the opioid epidemic exploded nationally, the face of who was suffering from addiction blurred. Suddenly, there was no face to the epidemic - everyone seemed to be addicted. As the stigma around addiction only led to more Americans dying, communities were left trying to grapple with how to address the crisis in the wake of governmental neglect and incompetence.

A Creative Solution

In 2017, Naselroad, along with the director of the Appalachian Artisan Center at the time, Jessica Evans, applied for and won a grant from ArtPlace America’s National Creative Placemaking Fund to start the Culture of Recovery in Hindman. Shortly thereafter, the Appalachian Artisan Center began working with the Hickory Hill Recovery Center and the Knott County drug court to offer training to people in recovery to learn luthiery, as well as blacksmithing and pottery.

“The infrastructure was here,” says Naselroad, “and we wanted to put it to use because it was just too cool of an opportunity to go to waste. As it turned out a lot of people needed a second chance.” They’ve even hired a couple of employees, including Nathan Smith and Jeremy Haney. Next year, they hope to hire more.

Naselroad has an innovative view of community development, not just in Eastern Kentucky, but nationally. “When you are looking at the assets and needs of a community, people who have been damaged or who are in need are often seen as a liability,” he says. But they are actually an asset. “If you put your infrastructure together based on need then the result is that you have a project that takes everyone in the community in a positive direction.”

The Culture of Recovery program bridges creativity with workforce development and healthcare. While the program very much helps those in recovery maintain sobriety, gain skills, and find work, it is what the participants did that really makes this program a win win for the community. Prior to the program’s creation not only was enrollment at the Appalachian School of Craft struggling, the beautiful, historic woodworking and luthiery factory downtown was falling into disuse. Now, as a result of the Culture of Recovery Program, Naselroad and the Appalachian Artisan Center are working to open its first instrument factory, under the Troublesome Creek Stringed Instrument Company, which will welcome tens of new hires in the coming years to the small town, and begin producing instruments for a national and international clientele. The work being done at the artisan center, the luthiery, and through the Culture of Recovery program is effectively bringing new industry into a region and people that have been forgotten or written off by American business.

“There is just not anyone coming here and offering jobs,” says Naselroad, “The coal industry stepped away from this area hard ages ago.”

Naselroad understands something few American entrepreneurs do about Appalachia: that despite historic struggles and the geographic challenges of the region, the workforce there is talented and eager to be trained and contribute to industry in America. This eagerness can be seen in the Troublesome Creek Stringed Instrument Company’s inaugural hires from the Culture of Recovery program.

“I was only supposed to be at the school one day a week for about two hours, but within the first three or four months I was coming two or three days a week and eventually I was coming everyday for seven or eight hours a day,” recalls Smith, “Every free moment I had, I was at the Luthiery. It eventually progressed to the point where I had some good skills built up and I was able to help other people who were coming through the program.”

Naselroad is also tapping into something deeply Appalachian: music. “Early on, music was an escape for me,” Haney says, “That is, in part, what drew me to the Hickory Hill and the Culture of Recovery program, more so than other programs. I liked that I could learn how to build instruments. It is clear to me that God already had a plan ready for me, I just needed to take that first step.”

Compassion For Those Struggling

“People have come to me and said, ‘Isn’t it risky hiring former drug addicts?’ And I respond, ‘It’s risky to hire anyone,’” explains Naselroad, “The people we have working with us now are people who are brave enough to start addressing their issues and we think that is a good place to start.”

To work in recovery, Naselroad has come to understand, is to meet people where they are at and have compassion for those who are struggling. While the stigma around addiction is still a problem in American society, American businesses are understanding more and more that they are the ones that are going to have to stand up and start addressing the issue through positive business practice. Having a job and a sense of purpose is a major pillar to successful recovery.

“The program gave me a sense of self worth and accomplishment,” says Haney. “That is something that you lose in addiction. You don’t feel like you are worth much. You feel like your life is a waste. But this program gave me a sense of purpose.” Now, he is sponsoring 5 other men in their recovery.

In the wake of an epidemic with so few signs of hope, innovative solutions are being found in the most humble of places and are providing a beacon for ways out of our collective national quagmire. The Culture of Recovery program is providing skills to people in need and creating passionate craftsmen who are keeping American culture alive and vibrant.

“As long as it’s open,” Smith says, “I will be here.”

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center