State lawmakers consider letting a North Idaho rehab program treat vulnerable children for addiction without a license

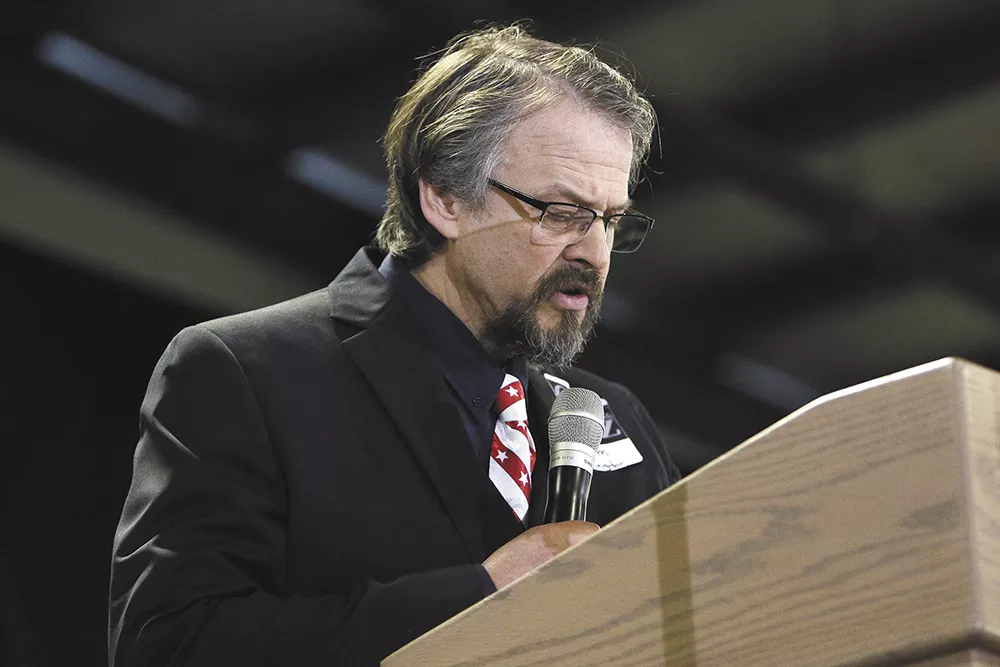

For years, Pastor Tim Remington ran an inpatient treatment center in Coeur d'Alene for teens battling drug addiction, taking a faith-based approach to treatment.

The problem? The program wasn't licensed to treat children, a fact that forced Remington to close Good Samaritan Rehabilitation off to teens in 2012.

But in Remington's view, he should be able to welcome vulnerable youth back into treatment, despite having no license. And he's repeatedly asked the Idaho Legislature to let him do exactly that.

"If we go the other direction and get certified, then I have to have people on board who are highly paid," he tells the Inlander.

And paying more licensed therapists, he says, means higher prices for families.

"People can't afford that," he says.

This year, the request from Remington — who himself was recently appointed as a state representative — has gained real traction. A slew of Republican state representatives, including Coeur d'Alene Reps. Mary Souza and Ron Mendive, pushed a bill to help Good Samaritan get around what they're characterizing as an unnecessary hurdle preventing kids from accessing needed treatment. The bill they proposed would allow Good Samaritan to treat teenagers as part of a pilot program, with no license needed. It passed the House and, as of press time, was being considered by a Senate committee.

But the bill has drawn strong opposition from those who feel there should be more oversight and accountability for a facility housing vulnerable youth — especially one where adults and kids in treatment for addiction stay under the same roof. There remains some mystery over what happens in the program, and how it treats patients who have different religious beliefs. While Good Samaritan lists internal stats suggesting the program is effective, one parent tells the Inlander that her adult son was court-ordered to go to Good Samaritan but was kicked out in part because he wasn't Christian.

Ruth York, executive director of the Idaho Federation of Families for Children's Mental Health, a nonprofit organization that advocates for youth, says licensing is a "really important process" and a safeguard for families.

"It assures that a facility has been through proper checks, has proper staff, proper safety precautions, and has been thoroughly vetted in being appropriate as a substance abuse treatment center," she says. "Any time you're dealing with kids under 18, that is just not a process to circumvent."

Remington, who readers might know as the pastor who survived a shooting in 2016, opened his Good Samaritan program to teens in 2005. It touts itself as a nonprofit that doesn't just focus on treating addiction, but also the causes for addiction. On its website, it says that "clients spend nearly every waking moment" learning about Jesus Christ, adding that "how the world treats addiction simply does not work."

Remington dismisses any concerns about oversight and accountability of his program. He notes that about 60 percent of the clients at Good Samaritan come there through a judicial order.

"We've got the whole community that's involved in it," Remington says.

Still, while the faith-based approach may work for many, at least one parent says it can be a problem if the patients aren't Christians.

Jessica Streufert, of Hayden, tells the Inlander that when her adult son was sent to Good Samaritan on a court order last year, Good Samaritan wouldn't let him participate in a six-month program because of his spiritual beliefs, even though she says he participated in all religious activities. After a judge again ordered her son into Good Samaritan, she says he relapsed and was arrested on drug charges. Now, he's serving a prison sentence.

In Streufert's letter to the Legislature, she adds that Remington once asked her "bizarre" questions about her sex life with her ex-husband before calling her son a "bastard." She urges lawmakers to not let Good Samaritan operate as a pilot program, saying she would be "petrified" to send a juvenile there, knowing what she knows.

"I just don't see how they can possibly pass anything like this," Streufert says in an interview.

Remington did not directly respond to a follow-up question regarding whether anyone has been kicked out for their spiritual beliefs. On the "bastard" comment, however, he says in a text message to the Inlander that he's "never used that word one time in 40 years. That did not happen. What does that mean? No dad???"

In an earlier interview, Remington says the goal at Good Samaritan is to build a family. For about seven years, Remington says Good Samaritan accepted teenagers who were 13 to 17. At most, it housed 10 kids at a time in four-month programs, while serving up to 10 times as many adults.

Adults and kids would stay in the same building — though Remington notes they had "separate quarters." The programs for the adults and the kids were largely the same and adults in the rehab program would act like a "big brother" for the kids there. Remington claims not one person has ever needed to be restrained in the years Good Samaritan has been open.

In introducing the bill earlier this month to make Good Samaritan a pilot program, Mendive says Good Samaritan self-reported a 78 percent success rate over a five-year period while costing a few thousand dollars for a four-month stay.

That's why Remington doesn't want to be forced to get a license, he says: He wouldn't be able to keep the cost down nor run the kind of program he wants.

"To be licensed, you need to have these particular people on staff," Remington says. "Now you have one or two doctors, a [master's in social work], going by their rules and you have to do this and that. It doesn't work like that for us."

That caught up with him in 2012, when a child's grandmother asked the state if Good Samaritan had a license to treat kids. The answer was "no."

"We had an attorney come up and say, 'You can't do this without a license,'" Remington recalls. "So we had to stop. We've been trying to get things going again [for teens] ever since."

Remington's request sparked a heated debate in the House this year. In a time when more kids need treatment options, proponents of the bill say, parents should have the right to choose one for their kid.

But some Democratic lawmakers and child advocates remained concerned on several points. For one, many providers have started to move away from residential treatment for teens, instead opting for outpatient treatment.

"There's no question we don't have enough services," says York, with the Idaho Federation of Families. "But the standard of care for youth with a substance use disorder is not to be residential. It is to be outpatient, and/or intensive outpatient. And those exist in North Idaho."

And if a place like Good Samaritan wants to provide those services, argues Rep. Lauren Necochea, D-Boise, "it can go through the proper process that protects our youth."

Secondly, York says that without it being licensed, parents have no due process if they suspect abuse. She also questions the lack of licensed therapists. Treating adults isn't the same as treating kids, and they need staff with proper training, she says.

"If you deal with teens in any way other than a trauma-sensitive and informed approach, you are not going to get a long-term remission," York says.

Other lawmakers expressed uneasiness about kids and adults commingling in the same facility, particularly because Good Samaritan's website says it treats porn and sex addiction. When asked about this, Remington tells the Inlander they no longer serve those people and they have no sex offenders there.

Remington says he's been trying to find a way to treat teenagers without a license ever since he opened the program in 2005. The original bill proposed this session by Souza and Mendive created an exemption in state law allowing Good Samaritan to do so. That was then amended to name Good Samaritan specifically as a pilot program. Rep. Barbara Ehardt, R-Idaho Falls, argued that should be sufficient to persuade skeptics.

"Don't shut it down, give it a try," she told lawmakers. "It is one pilot program. Give North Idaho an opportunity to help their children."

Remington says if lawmakers are so concerned about children, he says, they should look at all the complaints made at state-run facilities.

While supporting his bill to make Good Samaritan into a pilot program, Mendive says children are protected through the child protective act and "other statutes that protect youth." He suggests that there's an "inherent pushback on faith-based organizations."

"It's not like we're not worried about these children," Mendive says. ♦

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center