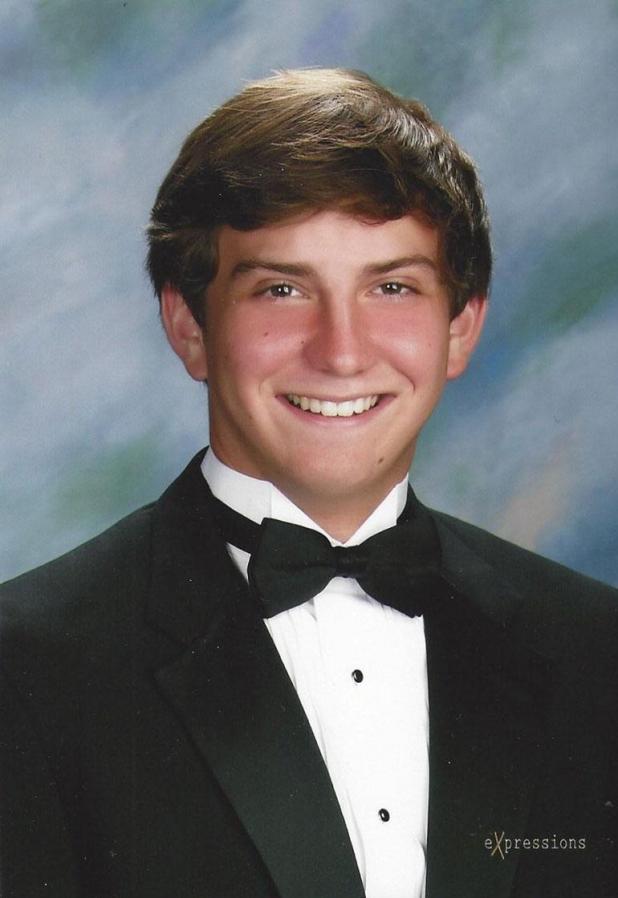

Opioids’ human toll: Young man died after unwittingly taking fentanyl

Graham Jordan, a 21-year-old LSU student, did not wake up one morning after partying at a bar in the Tigerland area near campus in 2017.The autopsy of Graham Jordan showed that Xanax had been in his system, but a deeper observation showed something much worse—traces of fentanyl, a dangerous compound that street dealers mix into other drugs to increase the high.

Fentanyl is an opioid that doctors use to treat severe pain. But it is so powerful, and it is becoming so common as an added ingredient in street drugs, that it is responsible for more than half of all opioid overdose deaths in some parishes.

The Centers for Disease Control say fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine and should only be used when pain is so severe that morphine will not be enough.

Authorities say the spike in deaths is particularly evident among younger adults in their twenties and thirties. Fentanyl use also is growing among high school and college students who buy other drugs such as Xanax, cocaine or heroin and do not realize fentanyl is present. Local officials say that one high school student in New Orleans died in 2019 from an accidental overdose of fentanyl.

Jordan, the LSU student, died after taking Xanax laced with a lethal amount of fentanyl. Mary Ellen Jordan knows fentanyl was not a drug her son sought out.

“I had never even heard of it before we got his autopsy report,” she said. “I don’t really think most people take that on purpose.”

Two of the state’s largest parishes, East Baton Rouge and Jefferson, have seen fentanyl use rise even as overall opioid use has leveled off.

In 2018, 102 people died from opioids in East Baton Rouge Parish, with 32 of them involving fentanyl. 2019 saw a total of 127 opioid overdoses. The number of those deaths involving fentanyl is unclear, but East Baton Coroner Beau Clark said illicit manufacturing of the drug has risen substantially.

Clark called fentanyl the “Russian roulette of drugs,” and Jefferson Parish Coroner Gerry Cvitanovich agreed.

“The buyer is counting on a drug dealer to titrate the right amount and not kill them,” Cvitanovich said. “What I’m told is a lot of customers will make comments like, ‘His stuff is so strong it killed two people,’ and that’s actually a selling point.”

Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, said there are many variations of fentanyl, and they can contain varying levels of dangerous chemicals, so people can never be sure what they are using.

Fentanyl is popular among drug dealers because of how cheap it is to produce and among users because it is more potent than heroin, according to medical professionals. Clark said the drug is too lucrative for dealers to resist, despite how lethal it is.

“There are so many people that are addicted that it does not matter,” Clark said. “You are going to make your money hand over fist regardless if your user dies.”

Cvitanovich said that in some cases a few grains of synthetic fentanyl are enough to kill a person and a pound of it could “take out the whole city of New Orleans.”

Cvitanovich said some teenagers begin stealing prescription pills out of cabinets at home and then buy pills illegally off the street after they go to college or move out of their family’s home. Sometimes this habit leads them to heroin or fentanyl.

“These people never dreamed of [shooting up drugs], but they wind up doing it so long as they can get high,” Cvitanovich said.

While fentanyl exists in heroin compounds on the streets, it also casually exists in pills at parties on college campuses.

Graham Jordan died several weeks after re-enrolling at LSU after skipping a semester.

Mary Ellen Jordan, a Mandeville resident, said she wanted to trust Graham and thought about sending him to rehab. She figured she could not do that since he was legally an adult.

“Once you’re 18, you have your own rights, and you can check yourself out,” she said. “You can’t be forced to go anymore.”

She knew Graham wanted to get better, but the presence of drugs was too difficult to escape.

After Graham died, she said, she heard from other parents and LSU students about how common it is for students to take various pills. Students may take drugs not just to get high, but to focus while doing assignments and to relax and get more sleep.

Clark, the East Baton Rouge Parish coroner, said opioids are common in many different settings.

“That’s what makes the opioid epidemic so devastating, because it affects both men and women,” Clark said, “It affects all races, it affects all religions. It affects everyone across the socioeconomic strata.”

Louisiana is making strides to combat the epidemic, especially in East Baton Rouge, the state’s biggest parish.

Clark sees the difficulty of stopping a drug as addictive as fentanyl but thinks it boils down to three initiatives.

First, the state must find a way to control the drug trade. Clark said most of the destructive drugs come from Mexico, and a stronger policing of the parish and at the Mexican border could keep the drugs from being easily available.

Second, even if the drugs are stopped from hitting the black market, doctors have to be more responsible in prescribing fentanyl. Baton Rouge is one of the leading cities when it comes to holding prescribers responsible as legislation limits how much of an opioid can be distributed at a time and who is allowed to prescribe them.

Hillar Moore, the district attorney for East Baton Rouge Parish, said his office has struggled to track down dealers because users are reluctant to give them up to police even after nearly dying from an overdose.

Finally, and most importantly, more money needs to be invested in rehab facilities to help addicts, especially since most drug dealers do not care what happens to their clients.

“Many of the dealers aren’t addicts themselves,” Dr. Clark said. “That fact makes them difficult to catch and bring to justice.”

Mary Ellen Jordan said that after Graham’s death, she looked through his phone and saw the GroupMe chat where the person who sold Graham the Xanax that killed him was still offering it to other students.

She said the LSU Police Department never asked for Graham’s phone to find the person who sold it to him. The department did not respond to multiple requests for comment about its investigation into Graham’s death.

“I know some friends of his, some acquaintances who are still doing some of that stuff,” Jordan said. “This would’ve been a pretty good roadmap to find the kid who did this. I really don’t think LSU really did anything to find this kid.”

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center