A Public Defender Fights to Save His Two Incarcerated Brothers From Covid-19

“Things are getting so bad here,” Lance Wilson wrote to his brother Jacque. “People are getting taken out of here on the daily because they are sick with the Covid-19 virus. They are setting us up for a death sentence.”

Lance is serving an eight-year prison sentence for his limited, addiction-fueled role in a prescription-drug theft ring, which he is serving at the federal facility in San Pedro, California, known as Terminal Island. The low-security prison sits on the water’s edge and is among the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic. According to the Bureau of Prisons, roughly 70 percent of the inmates housed there have tested positive for the virus and at least nine have died.

“Please help if you can,” Lance wrote. “I know there is so many more people that have it, but they are not testing us, they are keeping us locked up inside.”

As the coronavirus pandemic has spread through U.S. prisons, Lance’s letters to Jacque, a public defender in San Francisco, have grown increasingly desperate. In his first letter, dated April 18, Lance wrote to Jacque that there were 33 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and one death in the facility, and that inmates would no longer be allowed to use phones or computers until further notice. Three days later, he wrote that a friend had been taken to the hospital, and Lance, who suffers from asthma and hypertension, was concerned because of the crowded and communal nature of prison: “common bathroom, showers, water faucet and TV room,” he wrote. Please write back, he asked, “if you can, to make sure I’m still alive.”

Five days later, Lance reported that the warden had made an appearance, but didn’t have much to say — only that it would probably be another few weeks before they’d have access to the phones. “More and more cases of Covid-19 are popping up daily and it doesn’t seem like it is getting any better,” he wrote. “I sleep only 2 feet away from my celly.” As the days passed, Lance wrote again and again: The number of sick inmates kept growing, and he was increasingly worried about his own health.

Finally, on May 6, Jacque received the news he was dreading: Lance had tested positive for Covid-19. He was experiencing migraines, body chills, and night sweats. To date, he has not received medical care. “Things are out of control over here,” he wrote.

With Jacque’s help, Lance is now the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit filed May 16 against Michael Carvajal, the director of the BOP, and Felicia Ponce, the warden of Terminal Island, arguing that prison officials have failed to take decisive action during the unfolding health crisis by reducing the population of nonviolent medically vulnerable inmates, as the Department of Justice has encouraged them to do.

While federal law gives the BOP more than one way to release inmates like Lance, few of the thousands of potentially eligible inmates have been released. And in some cases, federal prosecutors have been actively resisting such efforts — including in Lance’s case. “The way that they’re treating these folks is inhumane,” Jacque said. Living behind bars amid the pandemic is “like being in a firing line. It’s just, when are they getting you?”

Screaming for Help

If things had gone according to plan, Lance might not have been incarcerated by the time Covid-19 began spreading through the nation’s prisons and jails. Although he’d been involved in a prescription-drug theft ring, the government concluded that Lance was just a bit player and recommended a four-year sentence. The judge on the case said he’d go along with that if Lance successfully completed a live-in drug treatment program first. Not long into the program, Lance was accused of having a contraband cellphone, which he denied. He was kicked out anyway. Although he successfully completed 20 days of a different drug rehab program, the judge doubled the recommended sentence to eight years. In contrast, the three principal players in the scam have already completed their sentences.

As the outbreak at Terminal Island worsened, Lance hoped for release. After all, Attorney General William Barr had directed the BOP to “immediately maximize” its ability to transfer “appropriate” inmates to home confinement — those who are particularly vulnerable because of underlying conditions, like Lance, and those incarcerated at hard-hit institutions, like Terminal Island — as a means to ease the spread of the virus.

Photo: Courtesy of Jacq Wilson

Arguably, the population of Terminal Island, writ large, falls into the category of those who should be considered for swift release. It is a low-security facility for low-risk inmates — a situation that actually exacerbates the spread of illness since the prisoners are mostly in large dormitory-style housing. It is also a designated facility for inmates with chronic medical or mental health conditions. Compounding the situation is the prison’s overcrowding. Designed to hold a maximum of 779 inmates, there are more than 1,000 living there, according to the lawsuit filed May 16 by the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, the Prison Law Office, and law firm Bird Marella.

“The remarkable size and speed of the Terminal Island outbreak is due to the vulnerability caused by a unique combination of three separate aggravating factors: overcrowding, communal living spaces, and vulnerability of the inmate population,” the suit reads. “Even under otherwise ideal conditions, this fact that the prison is already over capacity would render social distancing — a practice that inherently requires that facilities operate at far under their usual capacity — extremely difficult if not impossible.”

Still, Ponce, the warden whose responsibility it is to assess the population for release, has mostly failed to act. As conditions in the prison worsened, inmate families staged a protest outside the facility and local U.S. Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragán asked Ponce for a meeting. The warden didn’t respond for six days. When Barragán was finally given a tour, on May 1, she came away unimpressed: She could hear inmates in makeshift housing “screaming” for help, she told reporters, and was dismayed to learn that Ponce was only considering roughly 50 people for release to home confinement.

As Lance’s letters continued, Jacque decided that he had had enough; he wanted his brother out of Terminal Island. “A person should not potentially get a death sentence when they’re only in there for a little bit of drugs.” So he found a seasoned former federal public defender, Alyssa Bell, to file for Lance’s compassionate release, a process that has been somewhat liberalized since the passage of the First Step Act in 2018. Now, instead of having to wait for the BOP to signal that an incarcerated person should be considered for early release, the person can ask for it themselves.

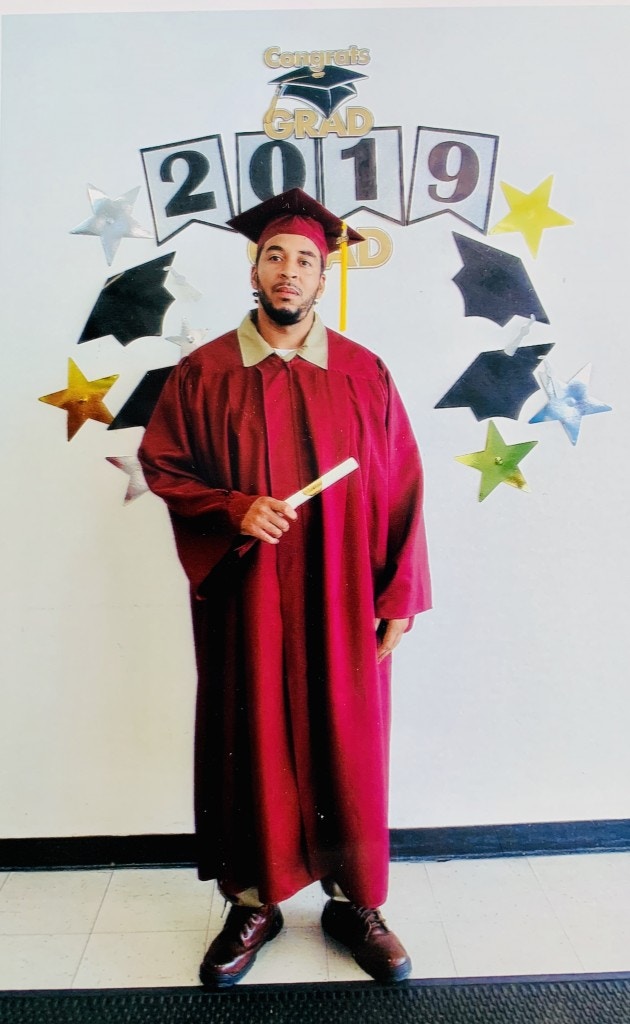

Lance filed a request with Ponce in late April. She still hasn’t responded. On May 5 — just a day before Jacque learned that Lance was infected — Bell filed his application in federal district court. Certainly, Lance would seem like a good candidate for judicial intervention. “He’s been the poster child for why someone should be released,” Jacque said. While incarcerated, he has taken numerous classes, become a facilitator for an alternatives to violence program, and hasn’t once been in trouble. On the outside, he has a home and a job to go to, and a young daughter and an elderly father to care for. “Mr. Wilson’s release plan demonstrates that he can, and will, be a contributing member of his community if granted a reprieve to live his life beyond the specter of illness and death that he must today confront,” Bell wrote.

Photo: Courtesy of Jacq Wilson

Federal prosecutors oppose Lance’s release. They argue that the BOP has done a bang-up job handling the pandemic, that Lance’s medical conditions are minor, and that the BOP has deemed him recovered from the virus — and as such, there’s no reason for his release. They argue that he is a danger to society and shouldn’t be rewarded with early release. “That is not a way to fight disease,” wrote Assistant U.S. Attorney Kathleen Servatius. “It is not a way to protect the public.”

Press accounts and court filings reveal that the government has repeatedly opposed release for incarcerated people like Lance, sometimes on technical grounds — including that the inmate filed for relief prior to the closure of the 30-day window that wardens are given to respond to individual requests. (In Lance’s case, the government initially made this argument, though the 30-day period has now elapsed without a word from the warden.)

Consider the case of James Bess, a 65-year-old nonviolent inmate in North Carolina who has diabetes and heart problems. He’d asked his warden for release, and the warden said no. Still, prosecutors told federal District Judge Lawrence J. Vilardo that even though the warden had already responded, the judge could not act until the 30-day window had closed, the Washington Post reported. It’s “not a perfect system, and frankly it wasn’t built for the circumstances we’re in,” the prosecutor told Vilardo.

“Come on, we’re human beings,” Vilardo responded and ordered Bess’s release.

Other prosecutors have argued that people like Lance can’t be released because they took plea deals and in doing so, waived a number of rights, including the ability to seek relief under the First Step Act — even though the legislation, and the rights conferred by it, didn’t exist at the time those deals were made. “It is impossible to ‘knowingly’ waive a right that does not yet exist,” Senior District Judge Charles Breyer wrote in an order releasing another California inmate.

Navigating a Crisis

In the best of times, navigating the criminal justice system can be a bewildering and byzantine affair. And the BOP is notoriously opaque in its operations and lacks meaningful oversight within the DOJ — indeed, even as Barr insisted the agency should “maximize” releases amid the pandemic, the agency has moved the goalposts, changing eligibility requirements for release, seemingly on a whim.

Given the desperate situation inside prisons, it’s no wonder there has been an increased sense of chaos amid the outbreak. Inmates have faced wide-ranging lockdowns and the BOP’s limited public responses about its operations and efforts to combat the virus are not terribly illuminating. For example, in reporting its Covid-19 numbers, the agency has categorized more than 3,000 incarcerated people — apparently including Lance — as “recovered” from the disease, but without describing exactly what that means. When asked about it by The Intercept, a BOP spokesperson responded that “recovered” means “no longer positive with Covid-19.” When asked if that meant those inmates had been retested, the reply was simply “for more information, you can visit the CDC website,” alongside a link.

Assurances that the agency is following well-defined protocols contradicts stories from inside the facilities where incarcerated people, including Lance, have reported not receiving medical care, that quarantine procedures have been loose at best — with people moved around inside facilities in a way that seems designed to spread infection — and that they have not been provided adequate cleaning supplies or personal protective equipment. Lance told Jacque that he’d been told he’d get one mask per week. That hasn’t happened. Instead, he’s reused the same mask for weeks. “They gave Lance a face mask — a paper mask,” Jacque said. “That’s like giving me a life jacket after I drowned.”

Even so, Lance is still in a better position than most: He has an older brother who is a veteran public defender with the skills and resources to advocate for him against the system’s powerful inertia. “This situation illustrates just how difficult it is for families to navigate the correctional system,” San Francisco Public Defender Mano Raju told The Intercept.

Photo: Courtesy of Jacq Wilson

Indeed, Jacque has been on the front lines agitating for change in the system for years, not only as a public defender, but also as a fierce advocate for a major change in California law that has helped to vindicate another one of his brothers who is again caught up in the criminal justice system.

For nearly a decade, Neko Wilson was jailed in Fresno County, charged with a murder he didn’t commit. There was no question about that. He was not even present when Gary and Sandra DeBartolo were robbed and murdered in their home in July 2009. But prosecutors contended that he was part of the underlying plot to rob the couple and, as such, was responsible for their deaths under California’s felony murder rule — a theory of accomplice liability that can dramatically expand the state’s power to punish individuals for crimes they never contemplated and had no role in carrying out.

Jacque joined forces with advocates and lawmakers to change the law and bar prosecutors from charging someone with a murder they had no direct connection to — and in 2018, they were successful. Neko was the first to be released under the new law.

But then, a wrinkle. In 2003 — six years before the DeBartolo murders — Neko and his wife were subject to a questionable traffic stop and search in Navajo County, Arizona, a rectangular swath of land northeast of Phoenix that cuts across the Hopi and Fort Apache reservations, as well as a portion of the Navajo Nation, which has been particularly hard hit by Covid-19. During the search, officers found marijuana, and Neko was arrested. He was given four years of probation, which was transferred to California. His arrest in 2009 for murder constituted a probation violation, so Arizona officials were supposed to issue a nationwide arrest warrant. This would not only signal to California that there was an outstanding criminal case one state over, but would also offer an opportunity for that violation to be resolved concurrently with the outcome of the California case. In other words, whatever jail time would be imposed based on the probation violation could be rolled into Neko’s time served in California. The law required Arizona to issue that warrant, but it did not, Jacque said, a violation of Neko’s due process rights.

In fact, it wasn’t until after Neko was released in California that Arizona put out the nationwide warrant for his arrest. Jacque drove with him to Arizona last spring to try to resolve the matter, but prosecutors balked, and a judge ultimately refused to set bail. The state is asking for a nearly nine-year prison sentence on the 17-year-old pot case. Neko has been locked up in Navajo County for nearly a year now as Jacque and a local lawyer fight for his release. The case is currently pending before the Arizona Supreme Court.

This was all frustrating, at best, before the pandemic, but as the public health crisis has infected the nation’s prisons and jails, both Jacque’s and Neko’s anxiety levels have spiked. Neko, like Lance, has asthma and he has not had access to a rescue inhaler while he’s been jailed. In response to inmate questions about personal protective equipment, a jail nurse told them that “the only way any of you are getting out of here is in a body bag,” Neko told The Intercept.

Across the U.S., jails have generally done a better job of reducing their populations amid the viral outbreak than have prisons. A typical jail has reduced its population by 30 percent, while prison systems have done so by just 5 percent, according to new analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative. And according to PPI, Arizona’s prisons and jails fall far below those norms. The state’s prison system has released just 2 percent of its population; at least two jails have actually increased their incarcerated population.

Finding information on the situation inside the Navajo County jail is difficult. According to the state health department, Navajo County has the state’s highest rate of infection at 1,206 per 100,000 people. County Sheriff David Clouse’s website contains no information about Covid-19 cases or efforts within the jail to contain the virus, though the White Mountain Independent on April 3 printed a statement from Clouse in which he assured residents that he and his staff “are working around the clock to ensure that we’re doing everything possible to mitigate the spread and impact” of the virus, “especially” in the jail.

Photo: Courtesy of Jacq Wilson

In an email to The Intercept, Navajo County Deputy Chief Ernie Garcia provided a bit more detail. Staff are assessed for symptoms upon arrival at work, and medical staff regularly screen inmates, he wrote. The whole jail is disinfected “hourly” using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-recommended protocols. Inmates processed into the jail are screened, and anyone showing “signs or symptoms” of disease is immediately quarantined. And they’ve looked at reducing the population “to create more space to help with social distancing.” As of May 14, five people had been deemed eligible for release, “if I remember correctly,” he wrote.

Just one inmate had tested positive for the virus, he wrote, but “he was positive prior to being arrested.”

Garcia’s depiction of life inside conflicts with Neko’s. He says the staff have rarely worn protective equipment, and although cells were restricted to two people for a while, they’ve recently gone back to three people per cell, with one person sleeping on the floor. There are not enough supplies to keep things clean, and he’s scared of getting sick.

On March 24, Neko’s attorney filed a petition in the local superior court, citing Neko’s underlying health risks and asking for his emergency release from custody. The court has yet to respond.

Meanwhile, Jacque is exhausted. And worried. Not only about his brothers, but also about his father, Mack. The 85-year-old is a Vietnam War veteran who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, which has intensified amid the pandemic — particularly after he learned that deaths from the virus had surpassed the number of casualties the U.S. suffered in Vietnam. In late April, Mack got to the mail before Jacque and opened a letter from Lance. It was the first one he’d read. He didn’t realize how bad things were at Terminal Island. Reading the letter, he had a panic attack and fell to the floor. Jacque had to help him up. All Mack could say was “I don’t want my son to die in there,” Jacque recalled. “Why is this happening to me?” Since then, Jacque has made sure all Lance’s correspondence comes directly to him.

Frustration and anger rise in Jacque’s voice as he contemplates the racism exposed by the pandemic. The virus has hit communities of color the hardest and has again revealed hard truths about the criminal justice system. “This is what happens when we have a system of mass incarceration,” he said. “If it’s not that you die on the streets as a young black man, from violence … you end up in prison, and you may die from coronavirus. All these things about race and inequality are just times 100 right now.”

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center