Abstinence, death and how to change the opioid epidemic

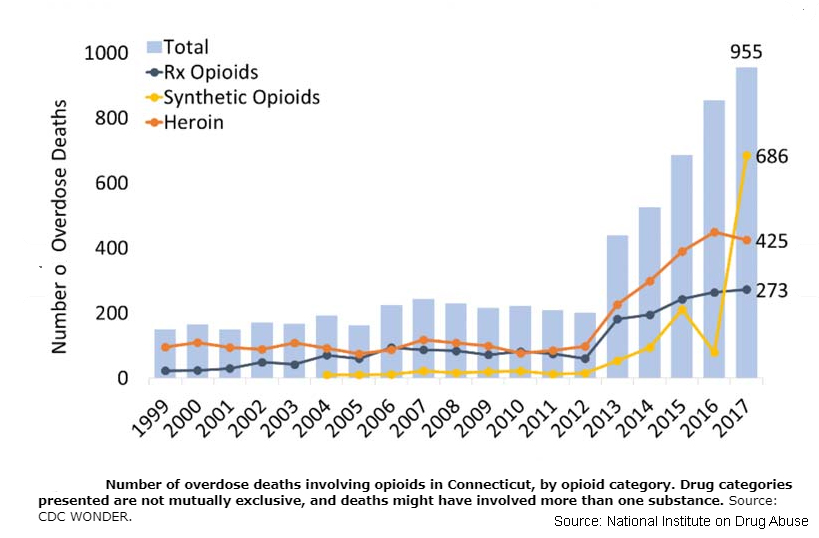

I chair death reviews. It’s part of my job as a medical director for a mental health and substance abuse agency. In recent years the bulk of deaths have been from opioid overdoses, now mostly fentanyl. The most-common themes are people who just left rehab, a detox program, or were released from prison. What has become clear is that abstinence-only approaches and programs for opioids don’t work, yet we continue to promote, practice, and pay for models that are ineffective and deadly.

While some opioid data is open to interpretation, certain figures hold up. Over the course of a year, about 80 percent of people who want to be substance free will have at least one slip, closer to 90 percent for people with more severe problems with drugs and alcohol and for those who also have mental health issues or have been incarcerated.

These lapse rates hold true regardless of the drug, from tobacco to heroin. But a lapse doesn’t equate to failure. It could be a one- or two-time thing and then they’ll return to their earlier goal to be substance free.

Here’s the disconnect. A lapse with alcohol, tobacco, or cocaine might be unwanted, but it probably won’t kill you today. Yes, cigarettes will eventually give you cancer, heart disease, and a stroke, and after 40 years of hard drinking, your liver dies… and so do you. But not today.

…abstinence approaches in the age of Oxycontin, black tar heroin, and now fentanyl are dangerous and, in the face of hard data, possibly immoral.

This is where opioids differ and why abstinence approaches in the age of Oxycontin, black tar heroin, and now fentanyl are dangerous and, in the face of hard data, possibly immoral.

Studies that have looked at 30-day abstinence programs for opioids show that over half their graduates relapse within a week of discharge, often on the ride home. Forty years ago, when the heroin on the street was less than 10 percent pure, that might not have killed you. But in our current epidemic, which involves high-octane fentanyls that start at 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, and carfentanil that can be over 10,000 times stronger, all it takes is two bags that cost six bucks on the streets of New Britain, Hartford, or New Haven and we have another death.

Daily opioid users become dependent on the drugs and develop tolerance. They need to take more drug to achieve the same effect, and should they go even a few hours without, they experience withdrawal symptoms that leave them sick, incapacitated, miserable, and craving. With traditional detox programs, people are weaned off the opioids, kept in a sheltered environment, and then discharged, often back to the same environment, stresses, and people with whom they used. Their tolerance to the drugs is gone, and a dose they once found safe is now fatal. Many parents who’ve lost children echo stories of how their child used a bag of fentanyl-adulterated heroin on the way home from treatment and it killed them.

But people like abstinence. I do too. How lovely if someone could take a problem behavior and just stop. And in those 80 and 90 percent relapse rates are 10 and 20 percent minorities who manage to quit and stay quit—some on the first try, some on the 15th. But preferences and likes that are not supported by data have no place in medicine and public health policy. Yet we continue to promote models of care that kill people with opioid use disorders.

Even though we know these are chronic conditions that will have lapses, we deny and restrict treatment based on positive drugs screens and the very behavior (drug use) that brings the person in for help. Nowhere else in medicine do we take such a punitive stance. I can’t imagine telling a person with insulin-dependent diabetes that if they continue to binge on Ben and Jerry’s, we’ll withhold their medication because by giving it to them we’re “enabling” their destructive behavior. We don’t do that. We work with that person—provide education, help them establish workable treatment goals, and nudge them along. It’s a harm reduction, risk-lowering strategy.

…preferences and likes that are not supported by data have no place in medicine and public health policy.

For those unfamiliar with harm reduction, it describes public health approaches to risky behaviors. Every time you put a seat belt on, you’ve performed an act of harm reduction. Yes, there’s still the chance that you’ll get hit on the highway, but you’ve improved your odds of survival. Harm reduction strategies for people who use drugs—including opioids— have been around for decades and include sterile needle exchange, rapid access to effective medications for opioid use disorders (methadone, buprenorphine, naloxone), overdose kits (naltrexone/Narcan), decriminalization of low-level drug-related behaviors, education, free condoms, and safe and supervised places for people to use their drugs so they don’t die if they get in trouble.

Outcomes from many studies are overwhelmingly positive, especially in countries who’ve used these approaches for decades. Results include greatly decreased rates of disease transmission (HIV/AIDs, Hepatitis), lower medical problems related to injection drug use, fewer deaths, fewer incarcerations, higher quality of life, and lower overall cost to the taxpayer.

In our current avalanche of overdose deaths treatment algorithms must consider the reality that most people will relapse. But they need not die because of it.

So, as we face a central question of our opioid epidemic, how do we turn back this tide of death? Answers stare back at us. We have to step away from abstinence-only approaches, such as arbitrary “three-strikes and you’re out” policies and detox protocols that don’t include the use of proven medications. And for those who continue to use street drugs and are not at the point of entering treatment, community outreach is key, and it needs to include access to sterile needle exchange, overdose kits (naloxone/Narcan), education about safer drug use, an open invitation to treatment that is readily available, and safe places for people to use their drugs.

Charles Atkins, M.D. is a psychiatrist, author, chief medical officer for Community Mental Health Affiliates (CMHA) in New Britain, Waterbury, and Torrington, and member of the Yale volunteer faculty. His most recent book on this topic is Opioid Use Disorders: A Holistic Guide to Assessment, Treatment and Recovery.

CTViewpoints welcomes rebuttal or opposing views to this and all its commentaries. Read our guidelines and submit your commentary here.

Free to Read. Not Free to Produce.

The Connecticut Mirror is a nonprofit newsroom. 90% of our revenue comes from people like you. If you value our reporting please consider making a donation. You'll enjoy reading CT Mirror even more knowing you helped make it happen.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center