America has an addiction crisis. ‘Digital rehab’ could help millions

Kara Nelson did not do everything right. She started drinking when she was 13 years old and soon hit the harder stuff. By 19, she was injecting heroin.

She struggled for years to get the right level of support to finally get off of heroin, methamphetamines, prescription drugs, and alcohol. She went to rehab twice. The first time it stuck and she was clean for three years. But then she slipped up and when she started using again, she says, it was much much worse. She tried rehab for the second time but it didn’t click the way it had before. In 2005, she entered prison on drug-related charges and was forced off drugs cold, a medically dangerous practice that is all too common. That is the only sort of rehabilitation she received during the two and half years she served.

At one point during her sentence, Nelson was transferred to a prison where, she says, there was a good substance abuse program—but she didn’t qualify for it, for reasons she can’t remember. The moment highlights a too-frequent problem for people who are addicted: there are few care programs to begin with and to get into one you have to tangle with red tape. Only 17.5% of the two million people addicted to opioids were able to get care in 2016, according to the National Institutes of Health.

On June 1, 2011, Nelson was released and began medication-assisted therapy using an opioid substitute called buprenorphine. She was on buprenorphine for two years, an unusually long time for most patients—and has now been sober for eight. Research from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and others shows that using such medication for longer spans of time makes for better recovery rates. Due in part to antiquated systems of care, this approach has not been adopted widely. Nelson is hoping to change that.

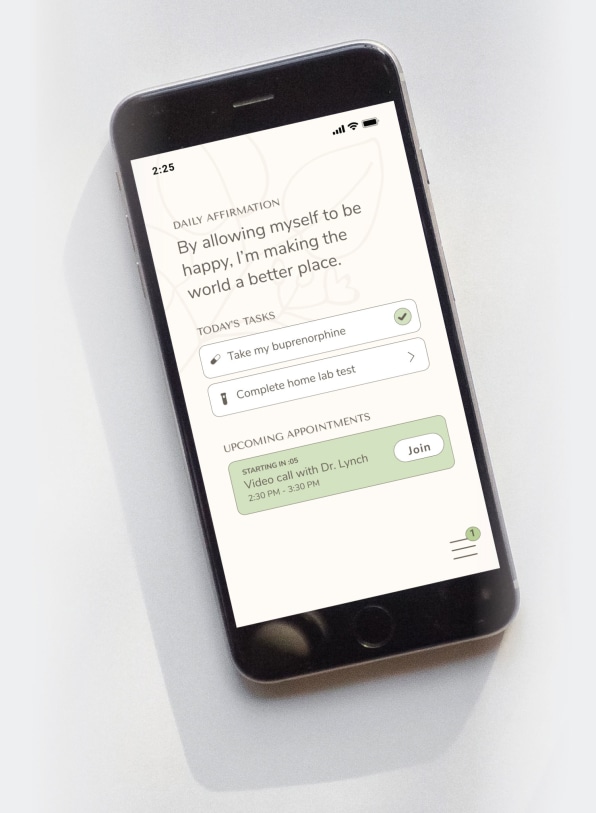

She’s joined a new company called Boulder which is launching a digital rehab program. Boulder uses both medication like buprenorphine and peer support to help people recover from opioid addiction. It has raised $10.5 million in venture funding, lead by Tusk Venture Partners, and signed a deal with the insurer Premera. The payer plans to give its members in Alaska access to Boulder in April and eventually expand to all 2 million members across the Northwest. Premera will pay Boulder a monthly flat rate for each patient so the company can tailor each treatment program to the individual and keep it going for as long as they need.

Bringing rehab to the masses

Telemedicine and online drug prescription represent an opportunity to reach people suffering from opioid addiction on their own schedule. Instead of traveling to a dedicated rehab center that may not be close to home, a patient can come to Boulder through a hospital. Once inside the hospital, a doctor hands their patient a tablet loaded with Boulder’s software, and the patient conducts their first session over video there.

Over video chat, a doctor will then determine whether the person is an appropriate candidate for treatment with Suboxone, a medication that combines both buprenorphine, an opioid pain reliever, and naloxone, which blocks opioid effects. If they are, the doctor calls in the prescription to a local pharmacy and then rush ships patients a kit with Narcane, a nasal spray version of naloxone that can bring someone back from an overdose, spit tubes for tests, and educational pamphlets to the patient. In an initial pilot in Southern Oregon, 85% of 100 patients stuck with the treatment program for eight months; 0nly one person went to the hospital because of relapse in that time.

Boulder CEO Stephanie Papes says part of the program’s success can be attributed to its ability to be responsive to patients’ individual needs. “We can ramp up care when they are going through something and go lighter touch when they are focused on getting back to school or spending time with their family,” she says.

Over the course of two weeks, a Boulder doctor develops an appropriate dosage for the patient, depending on other health factors, like if they’re pregnant or on antidepressants. Like any other drug, Suboxone comes with other side effects including depression and anxiety. In rare instances, it has been known to cause respiratory issues and liver damage. Even so, the resounding wisdom is that outside a few circumstances, like allergy, the benefits of these drugs for those suffering through addiction is greater than the cost. Once a physician determines a person’s Suboxone regimen, patients are expected to conduct spit tests to check that they are adhering to their medication and to see if they’re using other substances. While on video conference with their physician, a patient spits into a tube, which they then mail in. Alternatively, the patient records themselves doing the spit test and then mails in the sample. Unlike in other programs, where a relapse might get a patient kicked out, at Boulder, if a person relapses, the doctor adjusts the treatment accordingly. The hope is that by taking a less punitive approach, patients won’t be inclined to send in fake results.

It is historically difficult to get a prescription to Suboxone, because it is a controlled substance. The Drug Enforcement Administration policy states that it can only be prescribed in-person by an approved of physician or nurse practitioner. However, the DEA is currently working on policies that would let these healthcare providers prescribe Suboxone and similar medications over telehealth platforms. Once Suboxone can legally be prescribed over video chat outside the doctor’s office, a patient could come to Boulder with or without a visit to the hospital.

Changing the face of rehab

Though addiction treatment in general is not standardized, typical inpatient programs last 90 days or less and outpatient programs can vary even more. Where a digital approach has the biggest potential is allowing physicians to create personalized programs in terms of the duration of peer support, dosage of medication, and how long a person stays on medication.

Evidence suggests that longer term use of buprenorphine may help patients manage their disease better. A study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry in January reported that people who were on buprenorphine for longer (15 to 18 months) were less likely to seek out opioids in the six months after going off medication than those who were on it for less (six to nine months). However, the study also found that an equal number of people were relapsing and overdosing regardless of how long they were on medication. People with psychiatric disorders were particularly at risk of relapse.

The study gets at another problem inherent in treating addiction: medication is not a panacea. Addictive disease is chronic with a high rate of relapse, especially once medication goes away. “The literature shows that giving someone buprenorphine or methadone when they’re in the thick of it—as a technique to save lives—is clear,” says Fred Muench, who founded one of the earliest text-based programs for addiction after-care and now serves as president of the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. Medication alone is not a curative, he says. For example, medication does not teach someone coping mechanisms.

That’s why in addition to a doctor and medication, patients have access to a care advocate, who, much like a social worker, helps a patient with housing or finding a new job, and a peer coach, who offers emotional support as the patient works through sobriety. Unlike most treatment programs, this one has no end date. Patients can continue to be on Suboxone for as long as they feel necessary to mitigate their addiction.

The importance of behavioral therapy and coaching

Kara Nelson, who has now been sober over eight years, credits much of her sobriety to her network of mentors. “Every time I have flourished, every time I have been in the light of hope has been with peer support—people with lived experience speaking their truth into my life that I could relate to and trust,” she says. “Trust is super hard to come by when you’ve lived the lifestyle I’ve lived.”

Every time I have flourished, every time I have been in the light of hope has been with peer support.”

Kara Nelson

At Boulder, Nelson is going to give back some of that light she’s received as peer coach. She’s also helping structure what the role looks like. As the name implies, peer coaches are trained counselors who have been through addiction themselves. They provide a range of functions, from talking patients through cravings to supporting them through pregnancy and child birth. “We have a peer coach who helped provide one of our patients with actual physical resources to bring to the hospital when she was delivering and a note from her doctor that said she was on medication,” Payes says. All of the peer coaches for the Alaska program will be in Alaska, giving them familiarity with what 12-step programs and support groups are available to patients.

But some patients will need more than support groups. In the January study on long term buprenorphine use, 30% of patients had additional psychiatric disorders. Boulder does not have psychiatrists or therapists on its staff of care providers, but its insurance partner Premera plans to play a role in connecting patients to behavioral health near them. In addition to matching them to existing care providers, the company is hoping to fund new behavioral health facilities in rural communities through a series of grants worth a combined $15.7 million.

“In places like Alaska, there are not just access issues, there are climate-based barriers to getting care,” says Premera VP of product and solutions Rick Abbott, referring to the snow, ice, and limited roadways in the state. Those are in addition to financial and other socioeconomic issues patients may be facing, he says. “That’s probably every single barrier coming together to prevent you from getting care.”

Of the company’s 165,481 clients in Alaska, just over 1% suffer from substance abuse disorder. Premera and Boulder are still figuring out how long Premera will continue to pay after a patient stops checking in with Boulder’s physicians and peer coaches. This is complicated math: A patient can relapse or need to talk to a peer coach three years down the road out of the blue, sending them right back down the recovery path.

“Digital can only take you so far”

While the internet does much to bridge patients to care they may not otherwise be able to access, they will still have to find joy in their day-to-day life.

“Digital can only take you so far,” Muench says. “Ultimately what recovery comes down to is avoiding situations and people where you used to use and engaging with positive networks.” An important and sometimes overlooked facet of addiction recovery is the importance of community. Recovery often requires turning over a person’s entire life: finding new social circles, new hobbies, seeking out supportive family members, and leaving behind old haunts.

That’s probably every single barrier coming together to prevent you from getting care.”

Rick Abbott

Socioeconomic factors can also make recovery difficult even with the assistance of medication. For example, living in a state of financial duress or crisis is a stressor that itself can lead to relapse. Two-thirds of patients in Boulder’s initial pilot qualified for Medicaid. Another two of Boulder’s patients were homeless, another circumstance that might lead to relapse. In one case, the company was able to match someone with housing, though it speaks volumes about the state of social services at large that it could not find housing for both. There are limits to providing care over the screen.

To that point, while Boulder has shown an ability to keep patients engaged in its program, it has not shown how effective its platform continues to be once a patient has tapered off their medication. Papes says that even after patients have discontinued medication, they can still continue to check in with their peer coaches, care advocates, and physicians.

For Nelson, there will be a considerable push to connect the online with the offline. In 2015, she opened a housing and support facility for women coming out of prison called Haven House in Juneau, Alaska, where she now serves as the director. Through her long-time advocacy work she has met seasoned people she considers mentors, many of whom she’s introduced to Boulder to work as coaches. She says it’s important to involve people who know that recovery can be a wily thing. Not even she could have foretold that she would be sober for eight years now.

“Sometimes it doesn’t make sense,” she says of recovery. “Sometimes it takes that 101st try.”

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center