An increasing number of Colorado coronavirus patients are surviving, and fewer need ventilators

Back in March, one of the most pressing problems surrounding coronavirus was the fear that hospitals could run out of ventilators.

Doctors were quickly intubating patients, believing it was the best chance to save their lives from a contagious and deadly disease they had never seen before. But a lot has changed in three months about the treatment protocol for COVID-19 — use of the antiviral drug remdesivr, injections of convalescent plasma from recovered patients, and even the simple act of placing hospital patients on their stomachs instead of their backs.

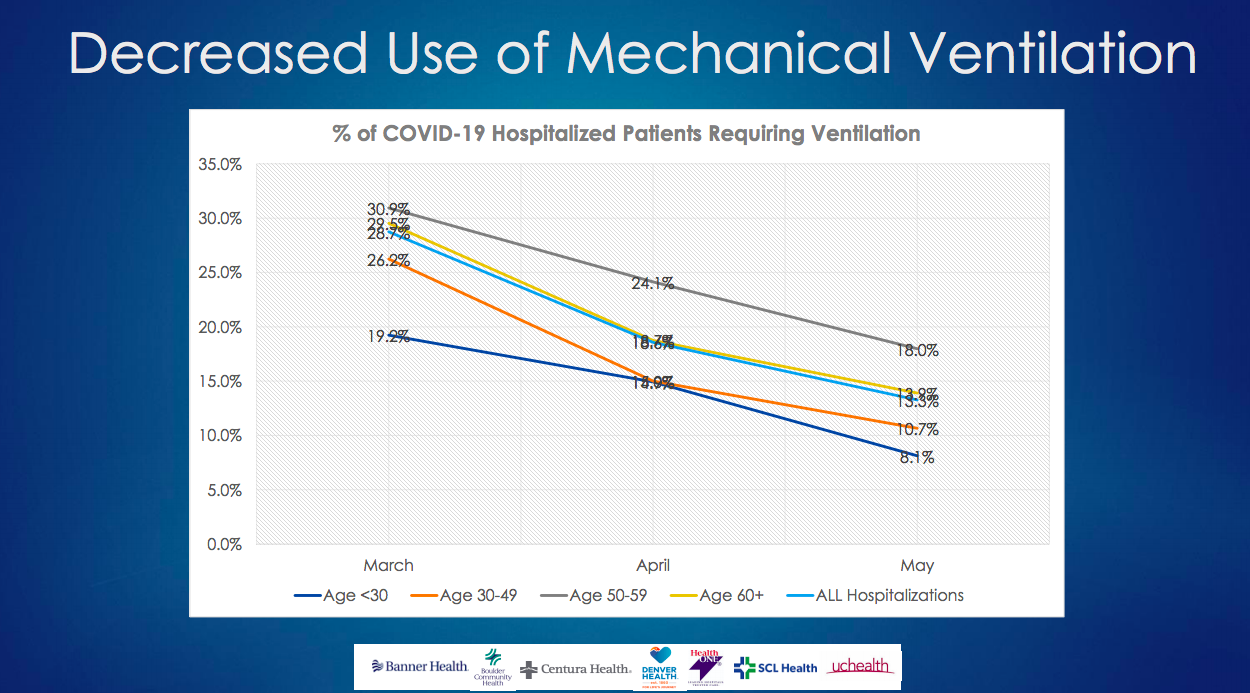

Now, as Colorado appears to reach the end of the first wave of the virus, new data released Tuesday from a collaborative of Colorado hospital systems shows just how sharply the use of ventilators has declined in this state, and how much patient outcomes have improved since the early days of coronavirus.

The data represent 96% of COVID-19 patients who were admitted to a hospital in Colorado from March 1-May 31. That’s a total of 4,903 patients across the state, all with a positive test for coronavirus.

Just 13.3% of hospitalized patients spent any time on a ventilator in May, compared with 28.7% two months earlier. And the average number of days a patient with coronavirus stayed in the hospital fell to 6.82 days in May, compared with 11.78 days in March.

The overall mortality rate for hospitalized patients — for all age groups combined — dropped to 10.5%, compared with 15.1% in March.

And by May, patients also were slightly more likely to leave the hospital and go home instead of going to a rehab center or skilled nursing facility.

The data collaboration is unique nationwide and the result of behind-the-scenes meetings among the chief medical officers of multiple health systems, including Banner Health, Boulder Community Health, Centura Health, Denver Health, HealthONE, UCHealth and SCL Health.

The study did not offer a conclusive explanation for why ventilator use decreased over the three months, but physicians pointed toward the use of other interventions, including convalescent plasma taken from recovered patients who have COVID-19 antibodies in their blood. Another main reason — physicians learned throughout the past three months that coronavirus patients can tolerate a lower blood-oxygen level than previously thought.

That means doctors are not intubating patients as early in treatment as they were back in March, instead allowing “permissive hypoxemia.”

“What we found is that these patients seem to tolerate a lower oxygen level in their blood and that has helped us to avoid mechanical ventilation,” said Dr. J.P. Valin, chief clinical officer for SCL Health, which includes St. Mary’s Medical Center in Grand Junction and Saint Joseph Hospital in Denver.

The reasons to avoid using a ventilator, if possible, are clear. For one, an intubated patient must be sedated and unconscious. There is a risk of lung damage, particularly when the patient needs high-pressure air. And, an intubated patient basically doesn’t move for days or weeks, leading to weak and atrophied muscles and a much more difficult recovery.

The average length of time a patient spends on a ventilator is one to two weeks, Valin said.

The patient data, which the hospital systems shared with the state health department this week, also showed that patients are leaving the hospital sooner — whether they used a ventilator or not. This means that other interventions are improving patient progress, Valin said.

There is no data yet, however, to show how well the antiviral drug remdesivr, which was originally developed to fight Ebola, is working on coronavirus patients. Clinical trials are ongoing.

The same is true for convalescent plasma, which was first used on a Colorado coronavirus patient in early April. Hospitals using the treatment are required to report their outcomes to a nationwide database.

While the Colorado patient data shows significant improvement in outcomes, Valin cautioned the general public about the takeaway of the study. It doesn’t mean that now is the right time to get coronavirus.

Already registered? Log in here to hide these messages.

Stay on top of it all.

Let us bring Colorado’s best journalism to you. Get our free newsletters.

“I wouldn’t want to encourage anybody to go out and get COVID to get it over with,” said Valin, who specialized in internal medicine. “We are seeing better outcomes today than we were a couple of months ago. We don’t have a vaccine and we don’t have a miracle cure.”

Physicians and researchers still have a lot to learn about the virus, he said. The study, for example, found that 2% of hospitalized patients under age 30 in Colorado did not survive, and there is no research yet to explain why.

The hospital systems involved in the research plan to dig down another layer to explore patient-level data, looking at other conditions such as obesity, smoking or diseases that might have played a part in patient deaths.

The chief medical officers of Colorado’s major hospital systems began meeting in mid-March, two weeks after the first case of coronavirus was confirmed in the state. They wanted to compare notes, to see how others were preparing for an expected flood of patients.

“At that point, very few people had taken care of COVID patients in the country, let alone Colorado,” Valin said. “After the first week, we suddenly realized this was bigger than one physician or one hospital.”

That first conversation quickly evolved into a daily, 8 a.m. call that lasted about an hour. The chief medical officers helped each other digest information rapidly coming from the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and local public health officials. Scott Bookman, incident commander for coronavirus for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, often joined.

Hospitals began reporting coronavirus data to the state health department in March, including patient totals and the number of patients using ventilators. But the data provided this week goes deeper, and will help hospitals statewide prepare for another possible wave of the virus in the fall or winter.

“We know we are at the end of the first wave of COVID,” Valin said. “There have been all kinds of predictions about what could happen in the summer or the fall. We want to be as best prepared as we could be, and we have learned a lot in the first round.”

Support local journalism around the state.

Become a member of The Colorado Sun today!

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center