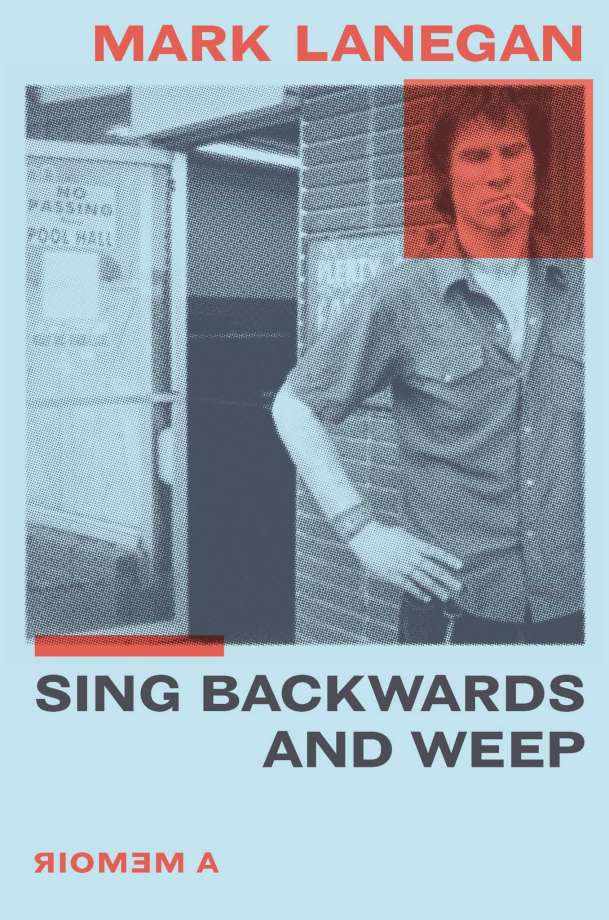

Book World: Screaming Trees’ Mark Lanegan delivers a nothing-but-warts memoir, full of drugs, alcohol and Kurt Cobain memories

Sing Backwards and Weep: A Memoir

By Mark Lanegan

Hachette Books. 352 pp. $28

---

In his fearsome and brutal new autobiography, "Sing Backwards and Weep," musician Mark Lanegan details his journey from small-town miscreant to the frontman of grunge-adjacent, mid-level rock band Screaming Trees, with heroin and sex addictions in tow.

"Sing Backwards" is a masterpiece of self-loathing and score-settling, a nothing-but-warts memoir that has more in common with books by Charles Bukowski and Jim Carroll than those by fellow musicians-on-smack Keith Richards and Motley Crue, which seem lighthearted by comparison.

Though Screaming Trees partly came up in Seattle during the early '90s, and "Sing Backwards" details Lanegan's friendships with Nirvana's Kurt Cobain and Alice in Chains frontman Layne Staley, it's much too internal to serve as a remembrance of the time.

"Sing Backwards" is at its best when examining the ruthless mechanics of a junkie musician's daily life: where to hide syringes - which were hard to come by, and often shared, in the days before needle exchanges - on a tour bus during border searches; the terrifying prospect of going through withdrawals during a snowstorm or transatlantic flight; how the citrus needed to break down European heroin can be found by scavenging lemon slices from abandoned hotel room service trays; and the various black, noxious fluids excreted by junkies in withdrawal, described in enough detail to chill even the most devoted gastroenterologist.

Lanegan grew up hard in a rough household in Ellensburg, Washington. By the time he left high school, he was a small-time hustler with a lengthy rap sheet and a drinking problem. Screaming Trees, a fledgling band assembled by local musicians Gary Lee Conner - Lanegan refers to him as "Lee Conner" throughout - and his brother Van, were his only ticket out of town.

Lee Conner is the book's Big Bad, a 6-foot, 300-pound rampaging lunatic with no social graces and a diva's sense of entitlement. He "projected an unwelcoming, unhappy, borderline scary presence," writes Lanegan, who often fantasized about strangling him.

The band soon signed with venerated indie label SST, and Lanegan moved to Seattle at the dawn of the grunge years. In a more conventional memoir, this would be the happy part of the narrative arc, where us-against-the-world bonds form between bandmates, touring is a joyful novelty and fame hasn't yet ruined everything. But even in the early days, life in Screaming Trees was a punishment to be endured.

Contemptuous of his bandmates and ashamed of the music they made, Lanegan lurched from one disaster to the next. He and the Conners were often in open, violent warfare with fans ("In those days, no one pressed charges"), club bouncers and each other. "The band was sick, violent, depressing, destructive, and dangerous," he writes.

A longtime blackout drunk, Lanegan soon found that heroin was the only thing to quiet his mind and deaden his urge to drink. As his habit grew, he guarded it jealously. "There was zero chance of anyone getting me to stop now that I had found my one true love, the only peace of mind I'd ever had," Lanegan writes. "As far as I was concerned, heroin had lifted me up from the grave."

Lanegan found a fellow traveler in Kurt Cobain, whom he first met when Nirvana played an early gig at the Ellensburg Public Library. Lanegan depicts Cobain as a gentle soul who remained a steadfast friend despite their increasingly uneven status levels. One day, Cobain withdrew thousands of dollars from an ATM and handed it, unasked, to his destitute friend, much to Lanegan's shame.

In turn, Lanegan helped save Cobain from at least one overdose, but his role in encouraging the superstar's own heroin use still haunts him. "Instead of being a positive influence on this guy I considered a genius and cherished little brother, I had become a facilitator to his undoing," Lanegan writes. In the days before Cobain's April 1994 suicide, he left voice mails for Lanegan, asking him to come over. Lanegan, hoping to avoid Cobain's wife, Courtney Love, didn't pick up the phone.

The grunge explosion powered by Nirvana briefly helped keep Screaming Trees' major label hopes alive, but whatever traction the band had was stalled by Lanegan's demons, which seemed to multiply. As Lanegan's band idled and his promising solo career withered, his heroin habit grew.

"Sing Backwards" devolves from a brutally candid tell-all to a numbing catalogue of miseries once Lanegan discovers crack. "I was a perfectly functional junkie for years," he writes, "but crack quickly took me to my knees." He began cooking and dealing the drug, sinking deeper into poverty, addiction and despair. He dodged the law, and multiple attempts at interventions. At one point, he and a homeless sex worker ran a prostitution scam from a mattress in his dining room (she is later murdered by a serial killer, a fact mentioned only in passing). He eventually became homeless himself, living on the streets until Love funded his rehab.

"Sing Backwards" ends with Lanegan leaving treatment, being taken in by Guns N' Roses' Duff McKagan, who gave him a job as caretaker of his properties, and by Josh Homme, his bandmate during the last days of Screaming Trees, who recruited him for his own band, Queens of the Stone Age.

In rehab, Lanegan - previously the kind of guy who rolled joints using pages ripped out of a Bible - experienced a religious epiphany, not mentioned again. He was changed, he writes, "maybe not by anybody else's God but by some very real force that intervened in the life of one sad piece of human roadkill the moment it was asked to."

---

Stewart writes about pop culture, music and politics for The Washington Post and the Chicago Tribune. She is working on a book about the history of the space program.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center