In Ohio, Epicenter of the Nation’s Opioid Epidemic, a Day in the Life of the State’s First High School Devoted to Students in Recovery

Over the next several weeks, The 74 will be publishing stories reported and written before the coronavirus pandemic. Their publication was sidelined when schools across the country abruptly closed, but we are sharing them now because the information and innovations they highlight remain relevant to our understanding of education

Columbus, Ohio

It’s an exciting day for any student: the first college acceptance has arrived. But for Alyssa, a student at Heartland High, a school for teenagers in recovery from substance abuse disorders, it was even more thrilling.

“I didn’t think I was going to go to college, and I didn’t care,” she said. She’s been showing off a printout of the text message of her acceptance to Bowling Green University to everyone — students’ phones are taken at the start of the day to minimize distraction. “It was very big that I actually got in.”

Alyssa, who plans to study nursing, is one of eight students in the inaugural class at Heartland, one of about four dozen recovery high schools across the U.S., and the first in Ohio. It offers personalized learning, daily mindfulness lessons, and group sessions to help students in their recovery. Crucially, it also offers a set of new friends, for whom trying to stay sober is also the norm.

There was a clear need for a recovery high school in Ohio, by many measures the epicenter of the nation’s opioid crisis. Ohio had the second-highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the country in 2017, the most recent year available, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accidental drug overdoses, the vast majority from opioids, killed more people than car accidents in Ohio every year beginning in 2007, ten years before that statistic reflected the nation as a whole. Recovery high schools, which have existed since the late 1980s but have grown rapidly since the early 2000s, were found to significantly reduce students’ substance abuse and improve mental health, according to a 2009 study.

Alyssa, the newly accepted college student, had trouble staying in school and had been in and out of different treatment programs. “By the grace of God, Heartland fell into my lap,” she said. “It’s one of the best opportunities I’ve been handed.”

All Heartland students spoke on condition that their last name would not be printed, and staff asked reporters not to ask triggering questions about their pasts that could jeopardize their recovery.

Though the need in Ohio is vast, what drove co-founder Laurie Elsass, a local realtor, to help open the school was more personal.

Her son, who died of an overdose in July 2019, became addicted to OxyContin in high school. After a stint in rehab during his senior year, he returned to school for a few weeks before graduation. Administrators didn’t want him to return to class, so he completed work alone in a computer lab.

“He was isolated, which is probably one of the worst things you can do to somebody who is struggling with substance use disorder,” she said. “They need to feel connected. Their disease really sort of makes them isolated, socially, and that’s very unhealthy.”

In general, there’s a rough schedule to the day at Heartland, currently housed in a revamped wing of Broad Street Presbyterian Church. The day starts with a mindfulness lesson, followed by classwork, recovery group and lunch provided by local business L Brands (owner of Bath & Body Works and Victoria’s Secret). After the meal, eaten in the church basement, students have recreation time, and then return to studying.

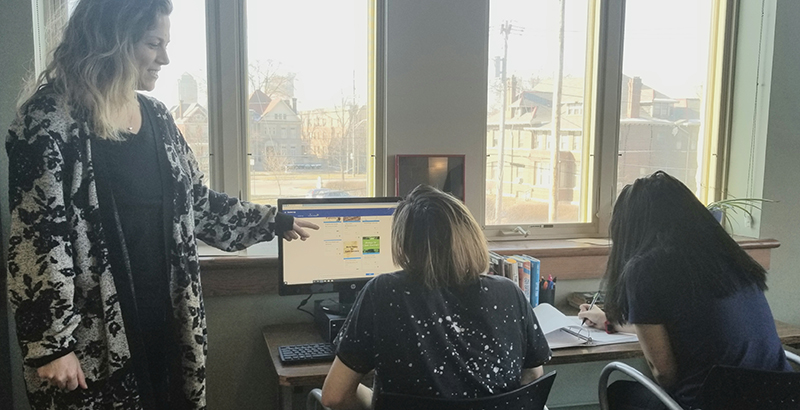

There are a few group lessons, but students mostly undertake a personalized curriculum, with staff helping students fill gaps in their transcripts. Alyssa, the newly-accepted college student, is taking chemistry and English classes online through a local university, while her classmate Konner is studying world history — currently his favorite era, the Middle Ages.

“Going to college really scares me,” because professors won’t be as lenient and understanding as the staff at Heartland, he said. Though he hasn’t made up his mind on a future career, a university degree is definitely a requirement for his top choice, therapist.

Students work extensively with Student Engagement Coordinator Jennifer Belému — better known as Sober Coach Jen. She’s in long-term recovery herself, for more than 20 years.

Before joining the founding team at Heartland, Belému was a recovery counselor for adolescents at a local treatment facility. She noticed a negative pattern: Her patients would get sober, then return to the same school environments where they had started using.

Students typically come to Heartland as transfers from public school or upon leaving inpatient or outpatient treatment programs. Some also are referred by local drug treatment courts, an alternative to the criminal justice system that keeps those addicted to drugs or alcohol out of prison, instead requiring them to obtain treatment. The option can lead to reduced or dismissed charges. Many students have been back and forth among several different placements before they get to Heartland.

The process of recovery is a broad one, encompassing behavioral changes and new routines, like recovery meetings (Belému will accompany students) and sober peer groups, and a physical outlet like yoga.

“Being sober isn’t just about not using,” Belému said. “We can have clean [drug tests], but that’s not enough.”

She’s an advocate of removing all potential addictions at once, even things like nicotine, sugar and caffeine. Just like all teenagers, though, the students at Heartland are fond of sweets: Chocolate milk and Pop-Tarts were popular snacks during The 74’s visit.

Students are drug tested randomly, and a few left school this year to return to full-time treatment. Those coming to Heartland “have to be committed,” but addiction recovery often isn’t a straight path, Elsass said.

“We all understand that the journey is not perfect. There are boundaries and guidelines in place, and we work with the kids to get them back on track if that’s what they need to do,” she said. “There’s some grace involved in the process, because there needs to be.”

The school itself has gone through some changes, too: The day The 74 visited in late October, the board had just ousted its founding executive director. The original head of school ultimately didn’t have the skill set necessary, Elsass said. She declined to elaborate further, citing confidentiality. Candace Greenwade, the new head of school, started in mid-January.

Looking ahead, many students hope to follow in Belému’s footsteps and join the recovery field: Peer recovery supporters, those who experienced addiction but don’t have the formal education of others in the field, are a growing part of the mental health landscape for those in recovery, she said.

Right now, tuition at Heartland is around $20,000 a year, but families are assessed on a sliding scale based on income, and full scholarships are available. No students are turned away if their families can’t afford it, Elsass said.

The school’s board hopes to convert the school to a charter down the road; they didn’t start that way because Ohio law requires schools to open with 25 students, and board members worried that having too many students would be “unmanageable,” she said. They also plan to raise funds for their own building.

“There is great need in other communities for what we’re doing, and we want to be a resource, and we want to see this duplicated because we know that the need is there,” she said.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center