Learning luthiery cuts string of addiction

HINDMAN, KY. -- The heritage of handcrafted stringed instruments runs deep in this tiny Appalachian village (pop. 770) stretched along the banks of Troublesome Creek. The community has been known as the home place of the mountain dulcimer ever since a revered maker, James Edward Thomas, known as Uncle Ed, pushed a cartload of angelic-sounding dulcimers up and down the creek roads, keeping a chair handy to play tunes for passersby.

Music is the region's lifeblood. But these strong cultural roots have been tested by the scourges that devastated eastern Kentucky, an early epicenter of the opioid crisis. Hindman is the seat of Knott County, one of the poorest regions in the United States and one that continues to grapple with overdose death rates that are twice the national average. It is also in the top 5% of counties most vulnerable to the rapid spread of HIV and hepatitis C, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The decline of the coal industry has brought even more economic hardship to these isolated hills and hollows -- providing fertile ground for Appalachia's signature epidemic.

But last year, an unlikely group of renegades -- suspender-wearing luthiers from the Appalachian Artisan Center here -- embarked on a novel approach to the hopelessness of addiction called Culture of Recovery, an apprentice program for young adults rebounding from the insidious treadmill of opioids and other substances. Participants, about 150 so far, learn traditional arts like luthiery -- the making and repairing of stringed instruments -- under the tutelage of skilled artisans. They come to the program through a partnership between the Artisan Center; a local residential rehab center for men, and the Knott County Drug Court, which is just down the block from the Appalachian School of Luthiery.

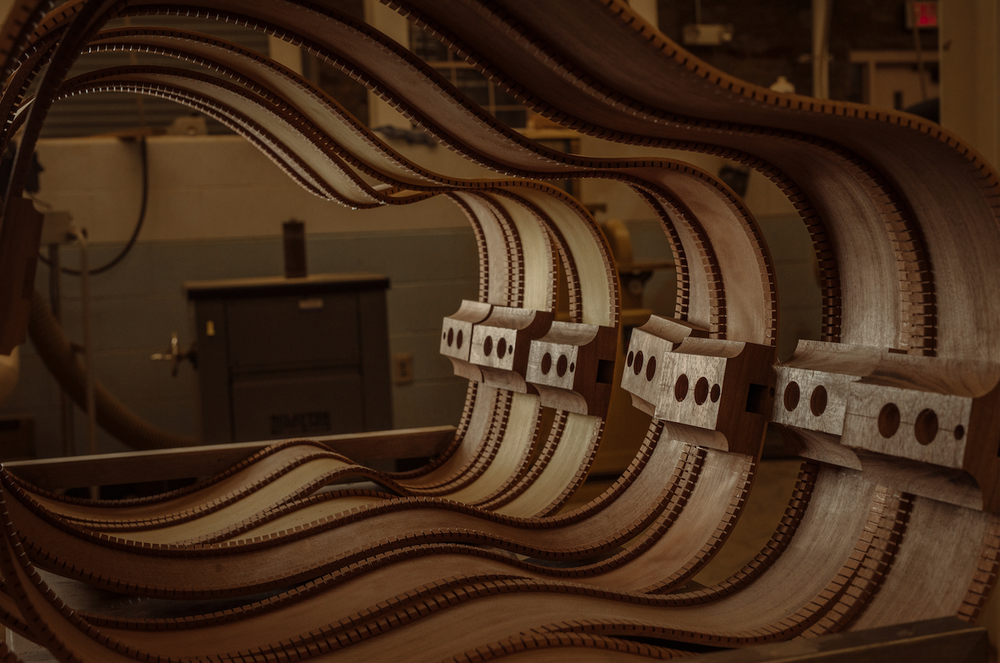

Unfinished guitar bodies are displayed at the Troublesome Creek Stringed Instrument Co. in Hindman, Ky. An apprentice program run by luthiers provides meaningful jobs and helps remove the stigma of opioid addiction. (The New York Times/Mike Belleme)

"We're dusty old woodworkers, not trained therapists," said Doug Naselroad, the master luthier who with a former colleague dreamed up the program. "But so many times now, giving somebody something to do has proved to be a powerful step in their recovery."

The factors that have led to the crisis here have followed a circuitous route like the hairpin turns on mountain roads. They include a sky-high poverty rate, a legacy of accident-prone industries, high incidences of childhood trauma, low educational attainment and a fatalism springing from a lack of opportunity and geographic isolation. These treacherous social determinants laid out a welcome mat for Big Pharma.

"That Oxy is vicious," said Randy Campbell, the Artisan Center's executive director, referring to Oxycodone. He drove up a steep road to the family cemetery where his 64-year-old brother, James Turner Campbell, was laid to rest from addictions to that drug and alcohol. "It grabs the educated as well as the noneducated."

The art of making an instrument by hand requires keen focus, attention to detail and commitment to a goal -- qualities that can help during recovery, in concert with therapy, peer-support groups and other rehabilitation work, experts say. The process is not linear: Most people relapse at least once, said Kim Cornett Childers, a Circuit Court judge in Knott County who presides over the drug court.

Some opt for other activities such as yoga, adult education or prayer groups. The power of Culture of Recovery, Childers said, is the re-connection with the region's resilient artistic heritage. "Many clients have never had anyone tell them they're proud of them, or done something they're proud of," she said. "Now they're creating something tangible and beautiful."

The results, albeit from a small sample, have been promising: About 94% have successfully graduated from the drug court, up from 86% before the program started. Most initially came to the court with indictments for drug possession, trafficking or burglary. The recidivism rate, which was already low, has dropped by more than half, with fewer people incurring new criminal charges, she said.

A TRANSFORMING PASSION

One of the graduates is Nathan Smith, 39. Now a tenacious and promising luthier, Smith was swept up in a typical pattern in which the physical demands of his job shoveling coal and operating machinery led him beyond his doctor's initial prescription for pain pills. He began buying them off the street -- "It helped me work and not hurt as much," he said -- and then started reselling pills to support his habit. The result was a drug trafficking charge, a brief stint in jail and then entry into the court's intensive, supervised outpatient treatment program, which lasts 18 months and often more.

Smith gravitated to luthiery, making his first dulcimer and apprenticing at the school for nearly a year. "I fell in love with it real quick," he said. "It is something I had a passion for that I didn't even realize."

He has been off drugs for two years and four months and is employed full time with the Troublesome Creek Stringed Instrument Co., a new nonprofit founded by Naselroad in partnership with the Artisan Center. Two of the company's six full-time employees are former Culture of Recovery apprentices.

Troublesome Creek hopes to garner enough orders for its instruments at a trade show now in progress to expand its operation and hire more committed Culture of Recovery apprentices. It offers a potential career path and the kind of meaningful work that pays a living wage without a college education. This effort is a rare economic beacon for the county and received an $865,000 boost from the Appalachian Regional Commission, which assists communities in 13 states affected by job losses from coal mining and related businesses.

The sprawling factory in a former high school is imbued with the aromas of red spruce and other woods. The density of Appalachian hardwoods compares with imported tropical rosewoods, Naselroad said. Though Osage orange and black locust have traditionally been used for fence posts, they have what luthiers call a great "tap tone." "The wood talks to us a little bit," he said. "It has to ring like silver."

TAPPING MOUNTAIN TRADITIONS

The name "troublesome" comes from the creek's propensity for flash-flooding. It is one of many memorable place names -- Mousie, Rowdy, Dismal Hollow -- found among the jagged cliffs around Hindman.

The main bridge is named for Jethro Amburgey (1895-1971), a dulcimer maker who taught generations of students at the historic Hindman Settlement School.

Amburgey was related to "Uncle Ed" Thomas (1850-1933), credited with pioneering the Appalachian, or mountain, dulcimer with its heart-shaped sound holes and an hourglass form one maker described as "shaped like a lady with a quiet and lonely sound."

Thomas was also a distant cousin of Jean Ritchie (1922-2015) from nearby Viper. During the 1940s to mid-1960s folk revival, she popularized the dulcimer in Greenwich Village and beyond. "Hey, what do you call that contraption?" Woody Guthrie asked her at the 1948 Spring Fever Hootenanny in New York, according to her book The Dulcimer People. "Why, you can get more music out of them three strings than I can get out of 12!" Ritchie set the stage for the dulcimer's broader embrace by musicians including the Rolling Stones ("Lady Jane") and Joni Mitchell, on her album Blue.

"Our workforce is dying," said Beth Davisson, executive director of the Kentucky Chamber Workforce Center, referring to government data showing drug companies saturated the state with 1.9 million pain pills -- roughly 63 pills per person per year -- between 2006-12, which were prescribed with wanton abandon. By 2018, statewide prescription drug monitoring programs were starting to have an effect, with overdose deaths beginning to decline slightly. But the abuse of prescription drugs, heroin and fentanyl remains a critical public health problem.

WITH SOBRIETY, HIDDEN TALENTS

The idea for Culture of Recovery was inspired by Earl Moore, 43, whose addiction began with buying OxyContin on the street, leading to several relapses, two suicide attempts and jail time for the illegal use of a credit card. His father left the family when Moore was young. "I took that personally," he said. "I found I could do substances and erase all that."

But Moore had an affinity for woodworking. He found out the Appalachian School of Luthiery had opened in town and approached Naselroad. "Earl said, 'I know you have a felony background check, and I'm not going to pass it,'" Naselroad said. "But he told me he thought it would save his life."

Moore apprenticed with Naselroad for six years, building some 70 instruments and forming a lasting bond. He went on to earn a master's degree in cybersecurity, his full-time career. "Addicts are the best hustlers," he said. "I've spun it to the good."

Kim Patton, 36, now the pottery instructor, went through the drug court after being indicted three times for trafficking. She was molested by a family member at age 14. "I never felt good about myself," she said. "Anything you asked the doctors for, they would give."

Now she turns recovering addicts toward pottery-making and sells her work on Facebook and Instagram. Culture of Recovery led her to discover "a talent you never knew you had till you got clean and sober," she said. Her T-shirt reads: "From Drug Addiction to Pottery Addiction." "Without art, God knows where I'd be," she said.

Artistic activities "can be powerful antidotes to distress, emotional violence and drug abuse," said Harvey Milkman, a professor emeritus of psychology at Metropolitan State University in Denver. They can help promote the brain's natural ability to induce pleasure, which is "better than dope," Milkman said.

Mike Nix, the program director at the Hickory Hill Recovery Center in Hindman, and a recovering addict, said that once the men "shake off the streets" with detox, they may be ready to learn a skill. About 85 residents have participated in Culture of Recovery one day a week since the program began, and it has been a positive complement to peer-led recovery, Nix said.

"Let's be honest -- these guys didn't get here on a winning streak," he said. "They come in pretty raw. It may seem small, but when they think, 'I'm going to build a guitar,' they take raw material from nothing and reach a goal -- some for the first time in their lives."

Style on 01/19/2020

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center