Opinion: Opioids saved my life. Quitting them took five excruciating years

The sweet, clean high of Vicodin, I will never forget. That exalted sense of optimism and quiet elation, the release from the troubles of life. Peace.

For years I needed it. I was born with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes nervous system dysfunction, extreme pain, debilitating fatigue and overly flexible joints.

My case of Ehlers-Danlos is particularly severe. At age 13, my feet, knees and back exploded in pain. I could hardly drag my tired body around school. By the time I was 20, I regularly begged for a guillotine for my neck agony.

By 2008 I had reached the limits of what I could endure. Instead of following through with suicide plans, I spoke with my doctor, who prescribed me opiates.

This was long before the opioid epidemic and subsequent government restrictions. Doctors back then still believed this was a safe way to treat chronic pain. I wasn’t offered another choice. What would have worked for pain like mine?

I was afraid. I knew these drugs were heroin in another form. But after I started, I instantly regretted having waited so long.

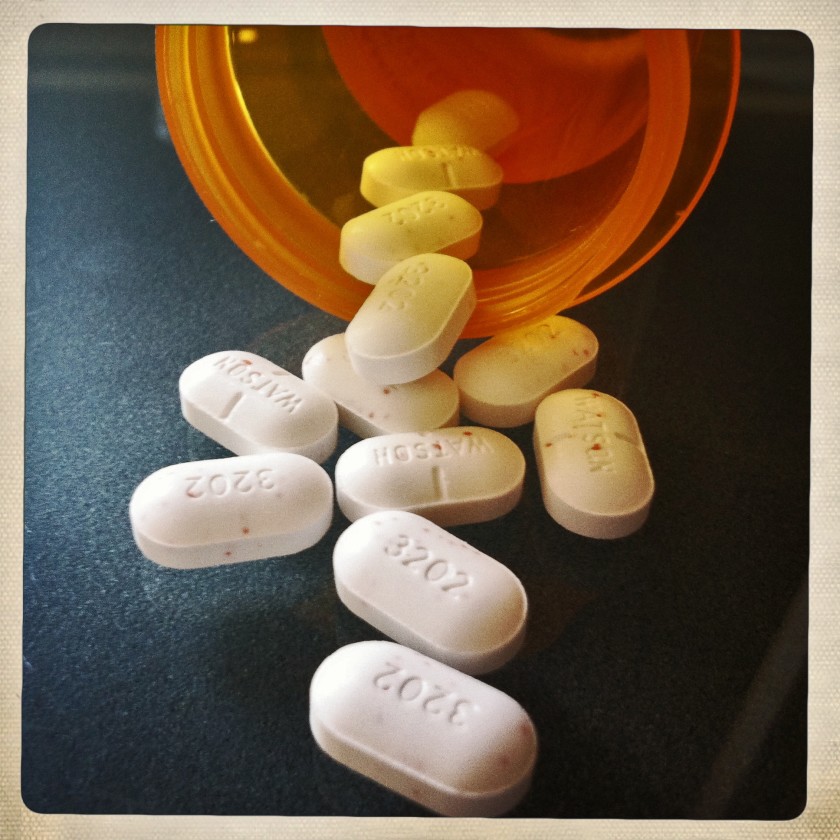

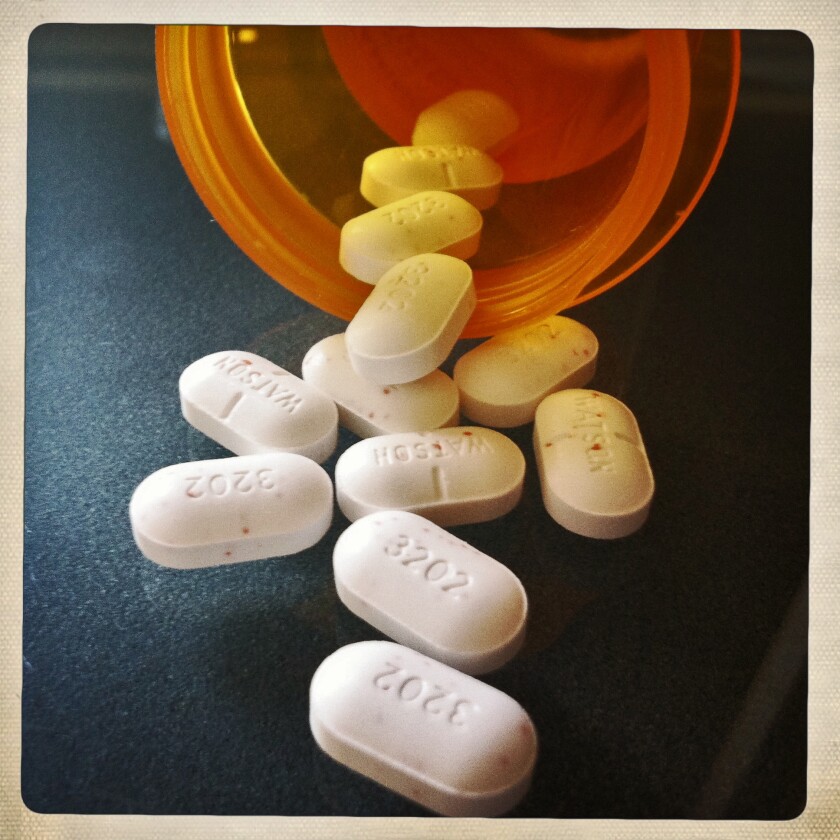

My prescription was for Vicodin and morphine paired with the muscle relaxant carisoprodol. I took this cocktail every night for six years, so I could sleep.

“You may never be able to get off,” my doctor told me as he wrote the first script for morphine.

What did “never” mean? I wondered but did not ask. It didn’t matter. There was no treatment for Ehlers-Danlos. I swore silently to myself that if I ever got lucky enough to get well, I would do whatever it took to get off.

At night, when I took my tiny pills, I was transported to a realm where there are no problems. It felt so fake, so obviously chemically induced, but deeply soothing, nonetheless.

Per the medical definition, I was not an addict. I was never drug-seeking, never doctor shopping, never secretly taking more than I said, never taking for emotional relief. I reduced my intake as my Ehlers-Danlos improved. As the result of an experimental treatment, my body became able to heal and build muscle. No more mysterious bruises. No more skin tearing. I went back to physical therapy, which had gotten me nowhere in the past. This time I progressed.

I asked the pharmacist for advice on quitting my painkillers.

“Go as slowly as you can,” she said.

So I tapered.

Acute withdrawal — when you still have drugs in your system but less than you are used to — started with nervous jitters, insomnia and stomach distress. Not too bad, I thought.

But soon every cell in my body screamed for Vicodin. In a life filled with pain, even I never knew such anguish could exist.

I couldn’t think straight. I surprised myself by yelling at people or bursting into tears over nothing. Every human interaction hurt.

My stomach got so bad, I thought I was dying. “Opiate withdrawal,” the gastroenterologist said.

I stopped titrating and parked my dose where it was, too sick to go lower.

How could such itty-bitty pills have such a hold over me? Then Philip Seymour Hoffman left rehab, overdosed and died. I put my head down on my desk and wept.

I understood.

::

Watching over the dope-sick is no picnic. My husband begged me to take a little more, just to ease the pain. I screamed at him for suggesting I go backward.

I went to the UCLA Pain Clinic for advice. Embarrassed, the doctor said, “You’re on such a small dose, why don’t you stay on for the rest of your life?”

That made me furious. I wanted to be free.

I made a chart and hung it on my refrigerator, my tiny reductions planned as aggressively as I thought I could execute. I needed to see there was an end.

I stopped trying to get anything done and steeled myself for the unending agony.

Finally, after seven months of cutting back, the last of my last tiny dose of opiates metabolized out of my body on July 4, 2014. I have a photo of that day: me, looking thin and grouchy-sexy-chic in my cowboy hat at a baseball game. My doctor texted his congratulations.

It was one of the most triumphant days of my life, yet the empty low was indescribable.

I did not know then — because no one had the guts to tell me, or maybe it would have been too cruel — that my withdrawal would only get worse.

I thought I had gotten to the finish line. I was only starting.

::

After I hit zero, I began counting again, this time up instead of down.

One week off. Two. Ten. Twelve.

Every single night I awoke, overcome with fear, disoriented and confused. Sleep deprivation devastated my health. Eventually I developed a drinking problem: the sad, all alone at night kind.

My marriage fell apart.

Ironically, my body never felt better. For the first time, I was able to travel. I swam miles in the ocean. I went back to work. Yet all those sweet firsts were ruined by the black hole opiates left in my brain.

I suffered for four years before my doctor discovered the research of Dr. Brian Johnson. His theory, that low-dose naltrexone could reverse the hormonal derangement and dysfunction caused by opioid use, worked. My post-acute withdrawal finally ended.

Do I regret my opiate use? Do I think I was misled? Was it worth it?

As someone born genetically destined to suffer, I don’t quibble over hypotheticals. It’s no one’s fault that chronic pain is so difficult to treat. I wish I’d had better advice for opiate recovery. I wish I could have gotten to my life now sooner, where I enjoy getting up every day and doing what I want. But I made it here because of the relief I got from opiates.

Yes, it was worth it.

Madora Pennington writes about living with Ehlers-Danlos at LessFlexible.com. She lives in Los Angeles.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center