Scientists Simulated a Sea Slug to Study Decision Making. Then It Got Addicted to Drugs

Stripped of any fancy circuitry and complex layers of higher order thinking, the nervous system is little more than a calculator for making smart choices. Food is good, but what if it's toxic? Empty calories won't give you energy, but what if they're satisfying?

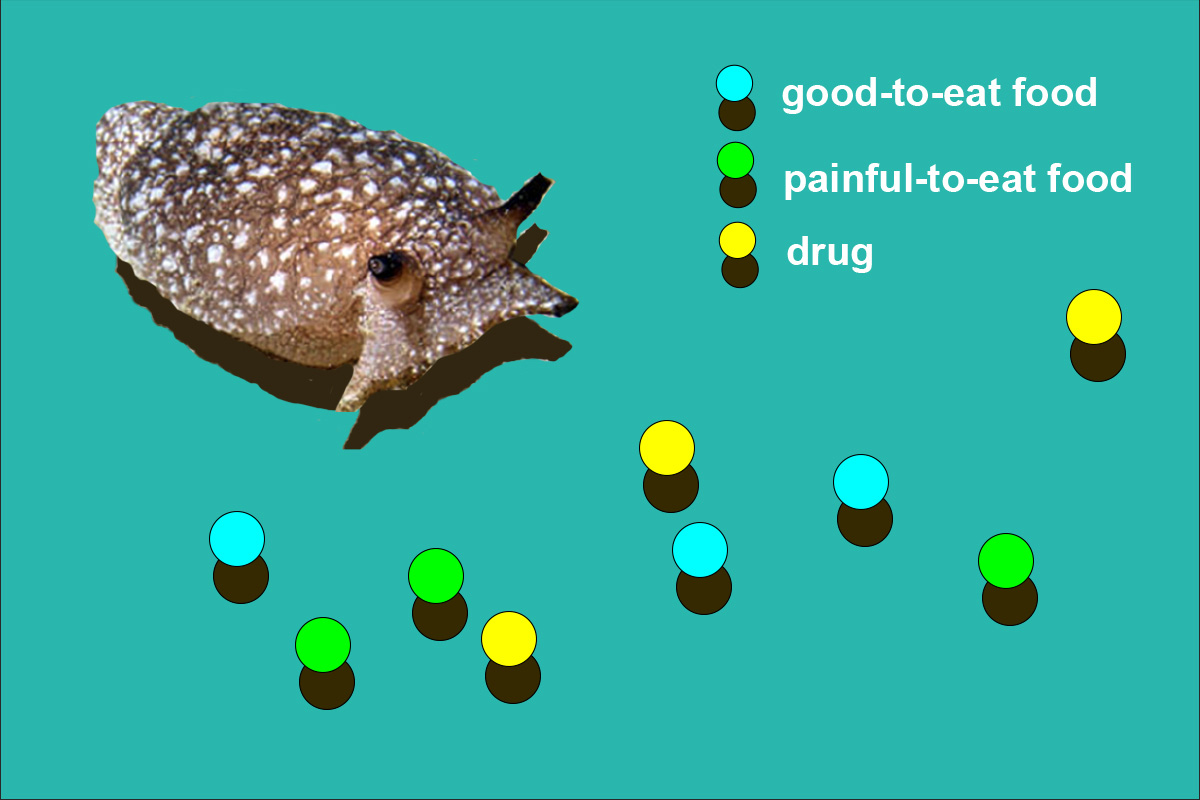

To better study how a rudimentary brain deals with decisions between competing interests, University of Illinois researchers digitally reproduced one of nature's simplest nervous structures – that of the predatory sea slug, Pleurobranchaea californica.

Then they got it high.

University of Illinois neuroscientist Ekaterina Gribkova is the researcher behind the cyerbslug program's most recent development.

Based on existing software developed to study behavioural motivation on a fundamental level, Gribkova's new version is designed with addiction in mind.

The artificial test subject was dubbed ASIMOV, after the renowned sci-fi author who wrote a novel or two featuring robots. (And because scientists are addicted to acronyms, it also stands for Algorithm of Selectivity by Incentive, Motivation and Optimised Valuation.)

Not unlike the cyberslug's existing artificial nervous system, ASIMOV's network of artificial nerves allow it to evaluate when and what to eat based on past experience.

This time, the program has software that represents an experience of reward. It can actually like what it eats.

"We wanted to actually recreate addiction in this organism," says Gribkova, who is the lead author of a study analysing ASIMOV's foraging behaviour.

"And this is the simplest way we could do it."

Working with fellow researchers Marianne Catanho from the University of California, San Diego, and Rhanor Gillette from the University of Illinois, Gribkova switched her pet slug's hedonistic setting to high, forcing it to limit hunger while seeking pleasure.

ASIMOV quickly learned to gobble up nutritious goodies while leaving any noxious nasties to one side. In times of extreme hunger, it would eat whatever it could get its hands on.

But the real test came when a third choice was included – a treat that had no nutritional value, which they called the 'drug'.

This new 'drug' option was designed to tick ASIMOV's life goals of fullness and joy, but only to a degree. Every time the slug indulged, its reward was a little less pleasurable.

"Just like when you drink coffee every day, you get used to the effects, which lessen over time," says Gribkova.

The slug's ability to neurologically adapt – what's referred to as homeostatic plasticity – soon caused the poor digital creature to crave more of its fleeting high, causing it to eventually seek the 'drug' all the time, to the exclusion of food.

"ASIMOV started going into withdrawal, which made it seek out the drug again as fast as it could because the periods during which a reward experience last were getting shorter and shorter," says Gillette.

The researchers kindly sent ASIMOV into cyberslug rehab. Without the digital drug in its pen, the program proceeded to get clean and regain its previous sensitivity to the substance's effects.

None of the addictive responses are in any way surprising, given we see them frequently in a diverse array of animals, not least ourselves.

But having a tested digital model to play with offers a practical and ethical tool to study the evolution of complex nervous systems.

Given the challenges of studying addiction in humans, having a solid starting place in systems like ASIMOV might one day provide insights into novel treatments or new kinds of therapy.

"By watching how this brain makes sense of its environment, we expect to learn more about how real-world brains work," says Gillette.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center