The US Already Has An Opioid Epidemic. The Coronavirus Pandemic Is Going To Make Getting Treatment Even Harder.

The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

Deaths from drug overdoses are likely to increase during the coronavirus outbreak because of disruption to recovery routines and access to treatment, according to counselors and people whose rehabilitation depends on daily care.

Lockdowns and social distancing have forced doctors, social services, and support groups to shut down, reduce hours, or move online — leaving people who use drugs and those in recovery to face greater risks with less support.

The coronavirus emergency has also presented new problems for people being treated for opioid use disorder — the medical term for opioid addiction — at methadone clinics. In order to collect their daily doses, patients typically have to go in person, which has made social distancing impossible for some. Service providers in New York, which is now the epicenter of the US coronavirus outbreak, say they don’t have the resources to handle delivery for all of the patients who are likely to become ill and require quarantine.

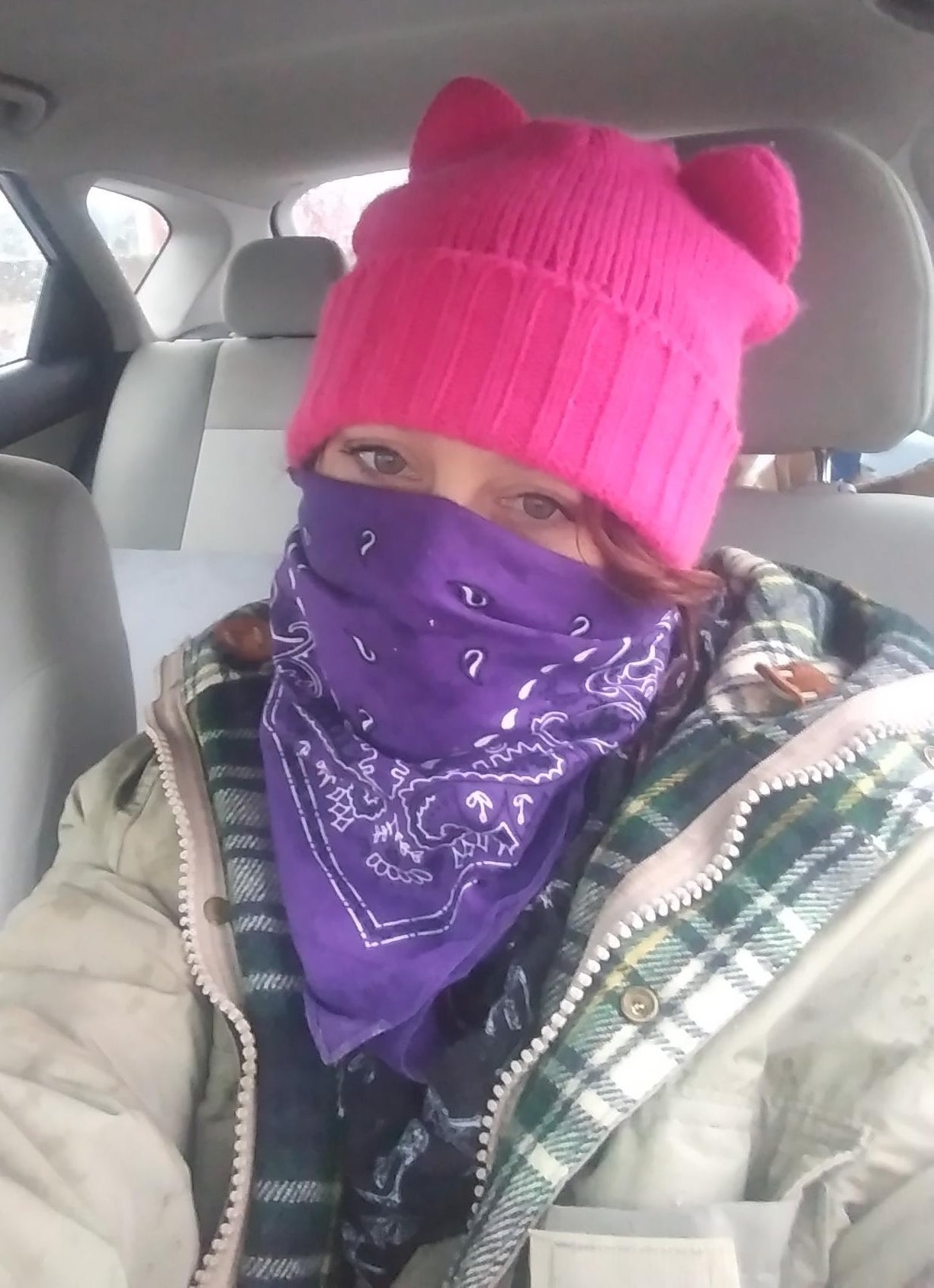

Patients have long feared what would happen if their treatment became unavailable. “This is stuff that in recovery folks that are on methadone talk about — ‘Oh my gosh, what if there was an apocalypse ha ha ha ha and we couldn’t get our doses,’” said Leslie Beckham, who has been in treatment programs on and off for six years, and now attends a clinic in New London, Connecticut. “It’s kind of a running joke a little bit, but now it’s serious.”

Courtesy of Leslie Beckham

Courtesy of Leslie Beckham With countries closing their borders and movement restricted, recovery advocates are worried that opioid use will become more dangerous. If supplies diminish, opioid dealers will likely be tempted to cut drugs with more dangerous substances, like fentanyl, even more than they do already. In an ideal world, this would lead to more people seeking treatment — but for many, the cost of the medication is prohibitive.

“The people who were getting help aren’t really getting any help right now at all. Put that on top of trying to stay clean, and you’ve got yourself one hell of a day,” said Danny Pont, who is part of an opioid treatment program in Rhode Island.

“I suspect there will be a lot of relapses — and with a lot of relapses, there’s going to be an uptick in overdoses,” Pont added.

Nearly half a million Americans have died from overdosing on drugs in the last decade, and preliminary CDC data suggests another 69,000 people died in 2019. The opioid epidemic was declared a national emergency in 2017, but advocates from across the country told BuzzFeed News they’ve never received the resources needed to fully address the crisis. Gary Mendell, founder of advocacy group Shatterproof, estimated the cost of adequate funding to address the crisis at around $50 billion a year. The federal government only spent around $7.4 billion in 2018.

If it was already difficult to deal with the opioid crisis on its own, facing it amid the coronavirus outbreak will be extremely challenging.

“I don’t think anything like this has happened before,” said Devin Reaves, who runs the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition. “I can’t remember a time in my life where there were actually two national declared public health emergencies.”

Methadone clinics and other medication-assisted treatments — like buprenorphine — for opioid use disorder have proven effective. But the medications are also subject to strict regulations over how and when patients can receive them, due to real risks of overdose, resale on the black market, and long-term stigma against the drugs, which some see as simply trading one addiction for another.

Courtesy of Danny Pont

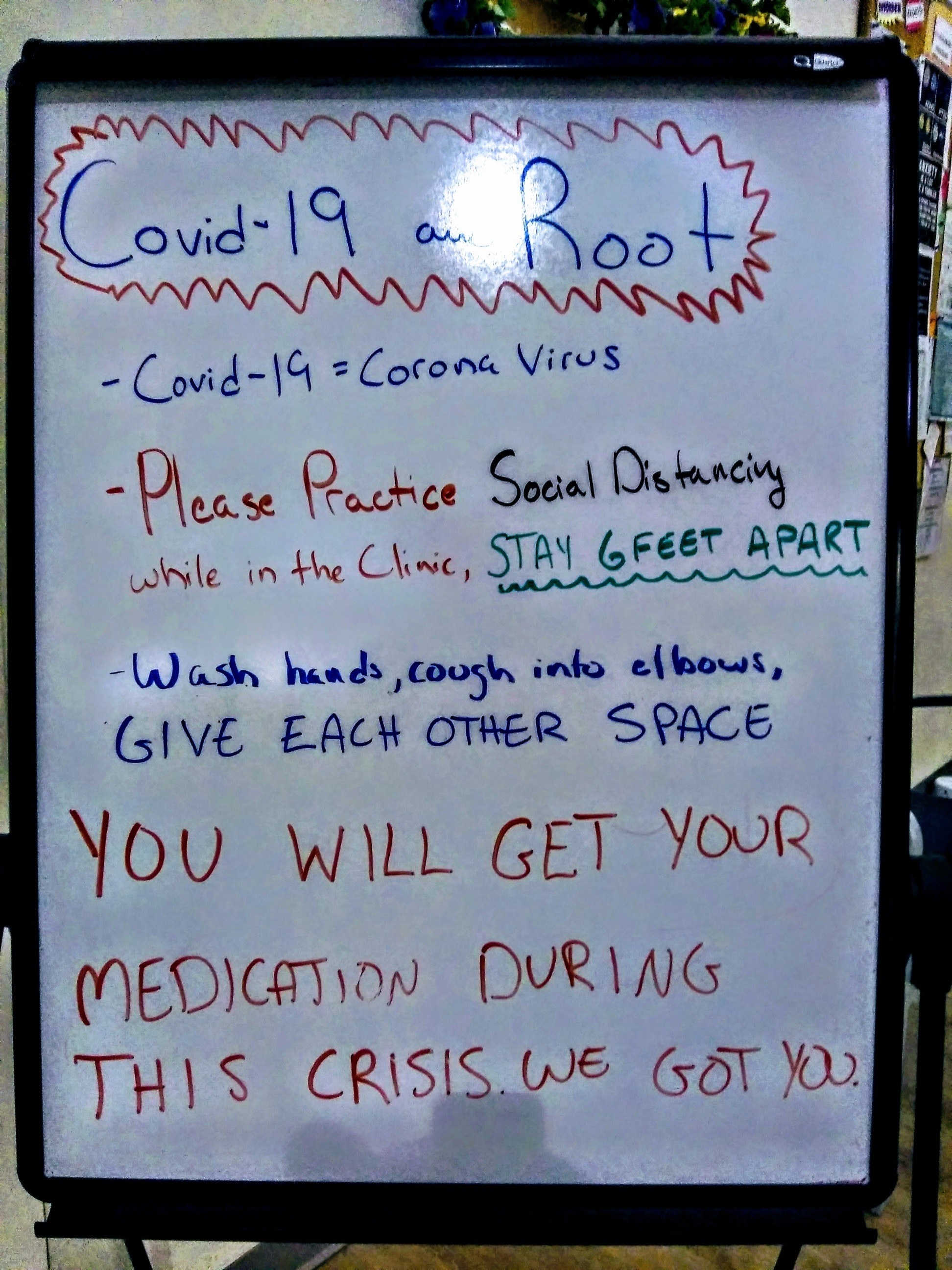

Courtesy of Danny Pont To combat these concerns, methadone patients are typically required to come in person each day to a clinic, where they may face long lines and drug-testing before getting their personalized dose, which must be taken in the presence of clinic staff. The coronavirus outbreak has created a new risk from the in-person nature of the clinic, and both patients and doctors who spoke to BuzzFeed News expressed concern about the need for social distancing.

In response to the outbreak, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration issued emergency guidelines on March 16, relaxing restrictions on medication-assisted treatment. The new guidelines allow doctors to prescribe buprenorphine via telemedicine, advise methadone clinics to give stable patients take-home doses in order to reduce crowding, and recommend delivery to patients in quarantine.

The changes have been a source of optimism for some advocates, who told BuzzFeed News that such measures are long overdue and hope they will become the new normal when the coronavirus pandemic ends.

Sarah Johnson, the medical director at Landmark Recovery, a network of addiction treatment centers based in Louisville, Kentucky, said she was blown away by the recommendations and saw it as evidence of government officials’ recognition of the essential role of medication in fighting the overdose crisis.

She said the changes were dramatic. “It’s like the Wild West,” she said. “In the matter of a one-week period, this went from one of the highest-regulated areas of medical practice to an area where there were lots of exceptions to rules that have been in place since the ’70s.”

But the new guidance has been haphazardly adopted and in some cases impossible to carry out, advocates say.

In New York City, where there are around 28,000 methadone patients, more than half could become sick and need to be quarantined over the coming months, according to Allegra Schorr, president of the Coalition of Medication-Assisted Treatment Providers and Advocates (COMPA) in New York. The new guidelines say that clinics should provide home delivery for anyone who doesn’t have a third party able to retrieve the medication. Given the restrictions, Schorr estimates that this would make clinics responsible for thousands of home deliveries, which she says is far beyond the capacity of clinic staff.

“That may be upon us very quickly,” Schorr warned, saying COMPA was seeking help from state and federal agencies to meet the needs of New York. “It’s the size and the scope that becomes so worrisome,” she said.

Opioids like heroin and fentanyl — and most of the medications used to treat addiction to those drugs — create a physical dependency in many people who use them, driving the need for a new dose or else risk going into withdrawal. If clinics are not able to find a way to deliver the medication, patients will either be forced to continue coming in person and risk spreading the coronavirus further or be left to face the consequences, which can include severe flulike symptoms, vomiting, diarrhea, and shaking, mixed with anxiety and depression.

Courtesy of Leslie Beckham

Courtesy of Leslie Beckham “It was like hell,” said Lesley Hann, who attends the same methadone clinic as Beckham in New London, describing her experience of withdrawal.

If getting medication becomes too difficult, some people may relapse and seek out drugs on the street. Anyone looking for heroin is most likely to encounter fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, which is the leading cause of the overdose crisis.

Hann said she had already seen long lines and crowding at her clinic, and that it had gotten so bad one day that some people decided it wasn’t worth the trouble. “I watched a guy and his girlfriend leave instead of waiting. They said, ‘Fuck it.’ He said, ‘I’ll just get it on the street. I’m not doing this.’”

Hann attends the clinic with her boyfriend, Tim Paprocki, and said they had each been given one day of take-home doses. Hann said she expected most people would simply have to keep coming to the clinic, even if they contracted COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, which would mean continued exposure for the rest of the community. “You just have to go,” she said. “If you were sick, it would not be an option to go without it.”

The situation for people in recovery is exacerbated by closure of numerous support groups and the stress of impending financial pressures. Pont, who lives in Connecticut near the Rhode Island border, said he had been temporarily laid off from his job at a junkyard.

“The pressure sucks right now. I’m just getting on my feet; I’m taking care of everything I need to take care of. And now I’m out of work,” said Pont. “And I’m like, fuck, how am I gonna pay for all of this. How am I gonna support myself?”

Pont said a local soup kitchen had closed, along with many of the Narcotics Anonymous groups in his area. There have also been reports of closures or reduced hours for syringe exchange programs in New Jersey, a recovery center in Texas, and outpatient services in Kentucky, among others.

Many of those groups have gone online — but service providers say many of their clients don’t have access to the internet or cell service, and such disruptions will put the most vulnerable groups at even higher risk.

Lisa Medina, a counselor in Austin who treats people with substance use issues, warned that the loss of community would likely compound trauma for many people. “Change, even chosen change, is terribly hard,” she said. “So many of those folks, they already have untreated trauma. So we’re going to see a secondary wave of trauma happening for many, many people.”

That instability is most dangerous for people who lack access to stable housing and may be especially hard hit by reduced services and social isolation.

“It’s a huge sense of loss,” said Shantae Owens, who is a community leader with advocacy group VOCAL-NY, and works with people who are homeless at the Alliance, a harm reduction center on the Lower East Side in Manhattan. The Alliance has continued to operate a syringe exchange program on reduced hours but was forced to close down its community space.

“When you take that from a person, it’s like, ‘Oh wow, now what do I do? I don’t really want to use, but that’s so depressing,’” said Owens, who explained that the closures and sense of isolation could trigger other traumatic memories. He added that he feared the crisis would lead to relapses for people seeking an escape.

Many of the social service providers and harm reduction groups that BuzzFeed News spoke to said they were scrambling to keep services available. But some argued that the hurdles created by the coronavirus outbreak revealed what they saw as the best way to tackle the overdose crisis: decriminalization. “If it was legal to have syringes everywhere, I could go make up 100 lunch bags and give them to people who need them,” said Caitlin O’Neill with the New Jersey Harm Reduction Coalition.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center