Two Medicaid fraud cases swirl around Powell treatment center

In December 2014, a therapist took a group of children from their Powell drug treatment facility into the Bighorn National Forest. Over the course of six hours, the patients cleaned a ranch, winterized cabins and carried trash out on a snowmobile, according to a note filed in the treatment center’s records.

Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center charged a government insurance program $112 per hour, per child, government and medical records show. For each child’s six-hour stint, the government insurance provider paid $672.

A progress note from the trip indicates a therapist’s plan for at least one child was to “continue providing opportunities to experience physical labor as a real-life expectancy.” This trip was one of at least a dozen to the ranch for “therapeutic” purposes. Though the trip was taken as a group, it was billed to Medicaid as community-based individual therapy for drugs and alcohol.

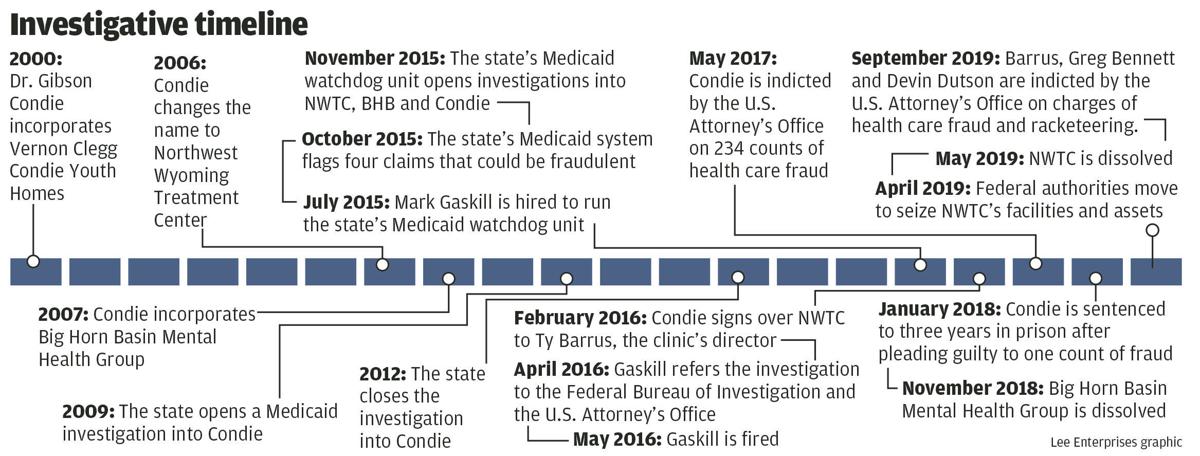

The Powell center charged the state for 70 hours a week per kid — all described as therapy. Medicaid investigators discovered that those hours, a therapeutic load that far exceeded treatment plans at other facilities, included the time the patients were sleeping, playing video games, sitting in class and working on the ranch, which was owned by the founder of the center. That man, Gibson Condie, would later be charged with 234 counts of health care fraud. He would plead guilty to a single count in 2017.

Over the course of about 21 months between 2013 and 2015, the state shelled out $4.4 million to the center for therapy for 47 juveniles, according to records compiled by a government investigative agency and provided this year to the Star-Tribune. More than $8.5 million for fraudulently billed medical care was paid out to the treatment center over six years, according to federal prosecutors.

However, that money would only prove to be a portion of millions worth of allegedly fraudulent medical bills submitted to the government for treatment in northwest Wyoming, according to state and court documents and the state’s former Medicaid watchdog. Condie, for instance, was accused by prosecutors of defrauding Medicaid out of $6.8 million. He agreed to pay nearly a third of that — $2.3 million — to the government as a condition of his criminal conviction.

In both cases the money came from taxpayers and Wyoming Medicaid coffers. But more critically, hundreds of pages of documents reveal the extent that patients — kids with drug issues, vulnerable adults and people with disabilities — are alleged to have been treated more as vehicles to make money than as members of Wyoming’s most vulnerable populations. Progress notes that were used to support Medicaid bills show medical providers were paid for therapy while the teens went to the gym and spent hours playing video games. In at least one instance, adult patients walked in a park and watched a demolition derby, an investigator said.

The cases have close connections in geography, the alleged methodology and personal and professional relationships. The total alleged fraud spanned a decade and covered not just the treatment center, but other areas of mental health care in northwest Wyoming, according to a Star-Tribune review of hundreds of pages of government documents and court case files, along with hours of interviews with the former state investigator who inspired the doctor’s prosecution.

The former investigator says, however, that the firing came as part of an attempt to slow his investigation into Condie. Gaskill’s allegation of retaliation has not been proven in court. He brought and then last year dismissed a set of civil claims brought against state government officials as part of a whistleblower lawsuit pertaining to the Condie investigation.

Star-Tribune requests for comment from federal prosecutors were largely declined on the basis of agency policy and ethical requirements preventing comment pertaining to ongoing criminal cases. According to a written statement provided to the Star-Tribune, however, state and federal law enforcement began investigating Condie as the result of a referral from Gaskill.

“Wyoming Medicaid’s Program Integrity Unit (which Gaskill led at the time) referred Condie and NWTC to the Wyoming AG’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit and the FBI. These agencies then opened a joint criminal investigation led by the FBI,” the U.S. Attorney’s Office for Wyoming said in an email. “This criminal investigation resulted in the indictment and conviction of Gib Condie, the civil forfeiture of NWTC’s property, and the indictment of Ty Barrus, Greg Bennett, and Devin Dutson. However, beyond making the referral, Gaskill was not a part of the criminal investigation or any resulting prosecution.”

The government insurance provider is designed to provide care to the poor, the unemployed and the disabled. It’s a joint program between the federal government and Wyoming that is among the largest pots of money on the state’s books. For fiscal year 2019, for instance, the state spent about $300 million on Medicaid. The federal government’s share was nearly $400 million.

On the other side of the exam table, a provider — a doctor, a psychologist or other type of health care provider — must also enroll with the state to be eligible to bill Wyoming for Medicaid services. If you’re not enrolled and approved, you don’t have a Medicaid ID and cannot be reimbursed for Medicaid services.

And finally, not all medical services are covered by Medicaid. Just because a patient is on Medicaid does not mean everything done for him or her is billable. Take the case of Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center: Documents reviewed by the Star-Tribune show the center was billing Medicaid for recreational activities, for educational services, for times the patients were sleeping, for travel time to and from the ranch and elsewhere.

“At every step in this complex case, which has spanned several years, the Wyoming Department of Health, including Wyoming Medicaid and its program staff, have fully cooperated with law enforcement and all other authorities. We will continue to do so,” Deti said in an emailed statement provided earlier this month. “We will also continue to be fiscally responsible with the public funds entrusted to the department as we serve the needs of Wyoming Medicaid clients.”

Even in Wyoming, the Medicaid system is sprawling. Seven hundred million dollars requires oversight. Enter the state’s program integrity unit. Gaskill took over the unit in 2015 and quickly zeroed in on Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center and a psychologist who was closely tied to it, Gibson Condie.

In a series of interviews over the course of this year, Gaskill described the various schemes Condie undertook to bilk Medicaid, to the detriment of the state and his Medicaid patients. Gaskill’s allegations are supported by hundreds of pages of legal filings and state investigative documents obtained and reviewed by the Star-Tribune. Condie is serving three years at a federal prison camp in South Dakota.

In court and investigative documents, as well as with interviews with Gaskill, Condie’s scheme comes into focus. He ran a company — Big Horn Basin Mental Health Group — out of his home in Powell. For years, dozens of people would provide “services” to Medicaid patients in Wyoming and bill for them through Condie. Think of these providers as largely unqualified freelancers who worked under Condie.

The “services” these freelancers provided ranged from psychological evaluations to acting essentially as babysitters for people with various disabilities, according to Gaskill’s investigations, federal prosecutors’ filings and internal government documents provided to the Star-Tribune. The “providers” who took care of these patients were not enrolled with Wyoming Medicaid, according to federal prosecutors’ filings, so they couldn’t bill for their services.

But with Condie’s Medicaid ID, the providers were able to get reimbursed by the state. In exchange for billing the services through him, Condie would take a cut — at least 10 percent, Gaskill said. Some of these other “providers” would just be paid a flat hourly rate by Condie, Gaskill alleged. Those activities are prohibited by Medicaid rules.

Gaskill’s investigation noticed something else: On all of their claims, Condie and Big Horn Basin wrote that their patients had depressive disorder. Indeed, over a roughly three-year review conducted by Gaskill’s office, Condie filed 7,307 claims for depression, an investigative document shows. He billed using only two other diagnoses, for a total of nine claims.

Condie claimed late in 2015 that he diagnosed all patients with depression because his training and education taught him that depression was often the underlying condition for substance abuse or other mental illness, according to notes from his interview with investigators. A medical doctor and state Medicaid official, in an email sent in March 2016 and later obtained by the Star-Tribune, called Condie’s understanding incorrect and said the psychologist was “hiding behind his degree.”

In a whistleblower lawsuit Gaskill filed in summer 2016 against Condie and others, he wrote that Condie “re-diagnosed each patient even though he had no records in front of him, had never seen the patients, and had no basis to assign this fraudulent code to a claim.” In other words, Gaskill said in an interview, Condie used the diagnosis of depression because the state Medicaid system was more likely to accept it.

As part of his investigation, Gaskill in 2016 spoke with one of Condie’s former providers, Nate Cook. Cook, who had contacted investigators with concerns, recalled being previously asked if the depression diagnoses were legitimate, and answered with his own prompt, “of course not,” according to a transcript of the conversation provided to the Star-Tribune. Cook had spoken with authorities about Condie’s fraud years prior, and he has not been accused of wrongdoing or malfeasance. Indeed, he told investigators he confronted Condie about the billing.

Over the three years reviewed by the state, Condie billed Medicaid well outside of a normal range. Gaskill’s investigation indicates the psychologist billed nearly triple the service that’s possible in a 24-hour period. Other than Condie himself, Gaskill said, no one was authorized to provide treatment through Big Horn Basin. Yet the company was able to provide 67 hours worth of service every single day for 1,035 days, Medicaid investigation documents show.

But, documents show, Condie and Big Horn Basin were not enrolled as a billing agent. The treatment center was enrolled in Medicaid as a provider. Not only that, but on the claims themselves, Big Horn Basin — Condie — would be listed as the treating provider, not the “freelancer” working underneath him.

The now-disgraced psychologist founded Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center in 2000 as Vernon Clegg Condie Youth Homes. The center would change its name in 2006 and would in 2016 officially distance itself from Condie. Much of the fraud Condie was accused of perpetuating was happening at the treatment center, too, court filings and state investigation documents contend.

Reams of progress notes show how the scheme worked. On March 16, 2014, one patient’s afternoon and evening were logged. Over those eight hours, the patient ate noodles, watched TV, played video games, watched others play video games, ate dinner, played more video games and then went to sleep. All eight hours were billed to the state using the Medicaid code for “comprehensive community support services for individual rehab.” None of those services could be legitimately billed to Medicaid in such a manner, according to the agency’s own rules.

The center in Powell was regularly billing for more than double that. What’s more, Gaskill alleged, the exact structured services that Whethem described weren’t laid out in any patient’s treatment plans at Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center. Whethem is not affiliated with NWTC and spoke to the Star-Tribune about general best practices.

Those numbers are especially significant when compared to other facilities around the state. Sheridan’s Normative Services Inc., for instance, offers a wider range of services than Northwest Wyoming Treatment Center did. It lost money last year. In 2015, the Sheridan facility’s profit margin was just 2.3 percent, according to federal tax filings.

What is known is that juveniles with substance abuse issues were sent to Powell for treatment, largely by way of court orders and other government recommendations. Instead of recovering from substance use issues, those kids became a vehicle to siphon funds away from Wyoming Medicaid, enrich Condie and, prosecutors now allege, fraudulently benefit three more men: Barrus, Bennett and a therapist named Devin Dutson.

A federal judge late last month unsealed documents formally charging Dutson, Barrus and Bennett. The three face a total of 15 criminal charges, which allege health care fraud, conspiracy and racketeering. In an indictment, prosecutors alleged that the men used the treatment center as part of a scheme to defraud Wyoming Medicaid out of $8.5 million between April 2009 and November 2015.

The federal government had the option to take over Gaskill’s whistleblower lawsuit, but declined to do so when a judge unsealed the case last year. Gaskill dismissed claims against Condie and Big Horn Basin Mental Health following the psychologist’s criminal conviction. The whistleblower, the former psychologist and federal prosecutors struck a deal to end that portion of the litigation. The exact details of the settlement were not available earlier this month; federal prosecutors could not provide documents governing the deal. A lawyer for Gaskill did not respond to a phone message requesting a more-detailed description of the settlement terms.

Condie, meanwhile, is expected to be released in September 2020. When he gets out, he will be responsible for repaying the government $2.28 million of his improper gains; a recent court accounting stated he still owes more than $2 million. Gaskill said a portion of the reclamation is due to him. The remainder will go to the state and federal governments.

However, following the conviction, Condie turned over to the government his remaining assets, which prosecutors have asked permission to use toward the restitution judgement. The assets include what remained in the psychologist’s bank accounts, multiple vehicles and the ranch children labored on years ago in the Bighorn National Forest.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center