U.S. surgeon general fights opioid crisis as nation’s doctor. But it’s also personal

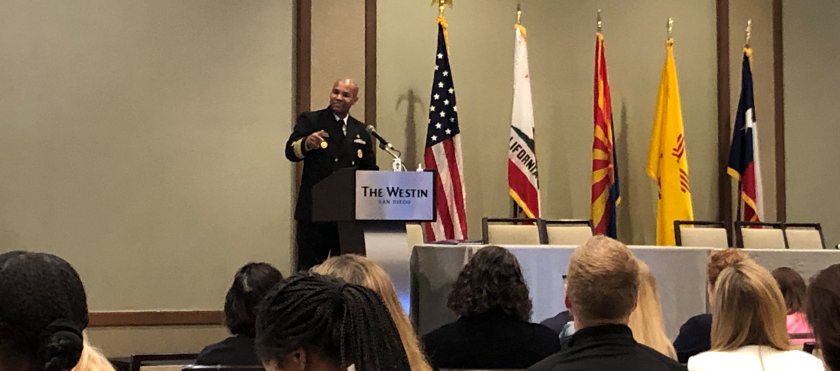

(Kristina Davis/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Kristina Davis/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

DOWNTOWN SAN DIEGO —

Drug addiction doesn’t discriminate.

No one knows that better than U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams.

While he is serving as the nation’s doctor, his younger brother is serving a 10-year prison sentence after stealing $200 to supply his drug habit.

“Addiction can happen to anyone,” Adams said Thursday to a roomful of physicians, law enforcement officers, treatment providers and policymakers at the Western States Opioid Summit in San Diego. “We grew up in the same family and in the same household.”

When Adams, an anesthesiologist, was first nominated by the White House in 2017, he wasn’t quite sure what to do with his family’s story. But by keeping quiet, he realized he would only be adding to the stigma surrounding substance use disorder.

“It was empowering when I finally started sharing my story,” Adams said.

He encouraged everyone else in the room to do the same.

“People often ask me what the biggest killer is. Is it tobacco? Is it sugary sweetened beverages? Is it drugs ?” Adams said. “I think our biggest killer in society is stigma, if we’re going to be honest about it. Stigma keeps people in the shadows, stigma keeps people from asking for help or even admitting they have a problem.

“Even folks here in this audience today at some point in life have refused help to someone with substance abuse disorder, either directly or indirectly by not endorsing a policy or practice because of stigma.”

Tackling the nation’s opioid crisis has been one of Adams’ top priorities as surgeon general, and he has sought to frame addiction from a point of empathy and compassion, one that moves away from a criminal justice approach to a public health approach.

“We know addiction is a chronic disease not a moral failure,” Adams said.

He has been at the forefront of encouraging the public to carry naloxone, a drug designed to reverse the effects of opioid overdose, issuing the call in the first Surgeon General’s Advisory in 13 years. While the antidote is now available in pharmacies and spreading in popularity, it is administered in only 5 percent of overdose cases, Adams said.

He gained attention in 2015, shortly after being appointed as Indiana’s health commissioner, when he convinced the state’s then-Gov. Mike Pence to allow a syringe exchange program to curb an HIV outbreak gripping a rural community. The infection cluster, about 200 cases in a town of 4,000, was being spread through drug injections.

Needle exchanges remain controversial, but Adams said he lobbied for support in unlikely places — local businesses, faith-based groups and law enforcement.

It’s an important lesson that needs to applied to the larger epidemic, he said. So often, the doctors, the providers, the lawmakers and the law enforcement aren’t in the same room, or speaking the same language, when trying to respond to the crisis. “We need real partnerships and we need collaboration.”

Meanwhile, the opioid crisis “is rapidly evolving and continually evolving,” from doctor’s offices to the streets as people in pain continue to self medicate, Adams told reporters later.

“We need to deal with the underlying factors — the adverse childhood experiences, the trauma, the lack of community resilience, the lack of focus on mental health and wellness — if we want to stop playing whack-a-mole.”

The number of overall drug overdose deaths continues to remain high, with more than 70,000 fatalities in 2017 — a 10 percent increase over the previous year, according to the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About two-thirds of the deaths are linked to opioids, with the biggest driver being synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which is commonly found in counterfeit prescription pills sold on the street.

In San Diego County, overall drug deaths fell slightly in 2018, but deaths attributed to fentanyl increased to 92, according to data released recently by the Medical Examiner’s Office. So far this year, that figure is at 94, said U.S. Attorney Robert Brewer.

Grayson Klehm, 26, became one of those statistics in 2017.

He was introduced to opioids at the age of 13 in the doctor’s office after needing surgeries on his elbow and knee. At 18, he was struck by a car while skateboarding and required back surgery.

“He was passed from pain management clinic to pain management clinic receiving more opioids,” said his mother, Lee Klehm of Escondido, who spoke to reporters at the conference. He ended up in jail, was in and out of rehab. He overdosed so many times — 15 — that his family prepared by learning CPR.

He had been sober for 18 months when, in an effort to avoid opioids, he bought a counterfeit Xanax pill. It was laced with fentanyl.

“It devastated our family,” said his mother, who shares her family’s story through the Hope2gether Foundation, a drug prevention nonprofit. “It can happen to anybody.”

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center