Why did Catherine Kenny and her best friend die in the same doorway?

The day after Catherine Kenny suffered a seizure in Belfast city centre in March 2016, she woke up in hospital. The first person she saw at her bedside was her sister Lee-Maria Hughes, who had been there for her all her life. “I said to her: ‘My God, sweetheart, what am I gonna do with you?’” Hughes says. “She just opened her eyes and said: ‘Will you help me? Please help me, I need help.’” She had never asked for help before.

Kenny had battled alcohol and drug dependency since her teens. Eventually, it had led to her sleeping rough on the streets of Belfast. Over the next few days, Hughes tried desperately to get her sister into rehab, but she did not succeed. Five days after her seizure, Kenny died alone in the doorway of a derelict shop just metres from Belfast’s magisterial City Hall. She was 32.

Kenny was the fifth person to die on Belfast’s streets that year, amid a mounting homelessness crisis in the city. Even more shockingly, newspapers reported that her boyfriend had died a few weeks earlier in the same doorway. An inquest found that Kenny died after a fatal reaction to the synthetic cannabinoid known as MDMB-CHMICA – nicknamed Sky High in Belfast. The inquest, held in January 2017, heard that 13 people had died from taking the drug in Europe between December 2014 and May 2016, and that Kenny was the first known victim in Northern Ireland.

The death of Kenny and the four other rough sleepers in Belfast led to a task force being set up to address the issue. However, in January 2017, the Northern Ireland assembly collapsed, and there has been no devolved government since. In the 18 months before March 2019, 205 homeless people lost their lives in Northern Ireland – more than 25% of the 800 homeless deaths in the UK catalogued by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism during the same period, despite the fact that Northern Ireland’s population of 1.9 million accounts for only 2.8% of the UK’s population. Northern Ireland counts homelessness and homeless deaths differently from the rest of UK, which explains much of the disparity, but the figures are still horrifying.

Hughes, a 39-year-old businesswoman, says that, if we had approached her last year, she would not have been ready to talk about her sister. She meets us at George Best airport in Belfast and ferries us in her BMW to the Welcome Organisation, a local charity that is the fulcrum of homeless aid in the city. Along the way, she points out the local landmarks – here is the liner-shaped Titanic museum and the Harland and Wolff shipyard, its giant yellow cranes, Samson and Goliath, dominating the skyline; there is the famous memorial mural to the hunger striker Bobby Sands. Hughes reels off the history of her home city in a series of well-turned anecdotes. She is small, fierce and warm.

When we enter the Welcome centre, we are confronted by a distressed young woman who has been stopped from entering the building because she has drugs on her. Through her tears, she says something about seeing someone who raped her in town, but we are ushered upstairs before we can learn more. Later, Hughes tells us that her sister would soon have calmed the woman down. “She’d have took that wee girl under her wing and settled her, pacified her, done everything for her. That’s just the type of person she was. She was amazing.”

Inside the Welcome, we are joined by its chief executive, Sandra Moore, a friend of Hughes’s who worked closely with Kenny. Moore is a passionate woman in her 60s who weeps one minute as she reminisces and purples with indignation the next when railing against the lack of funding for Belfast’s homeless people. Because public spending has been slashed, Moore says, charities have become increasingly dog-eat-dog as they compete for the tiny pot that remains. “At ground level, we can see people starting to jostle for what funding there is out there, as opposed to working collectively to address the issues.”

What is 'The empty doorway' - the Guardian series on people who died homeless?

Show Hide726 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2018, according to the latest ONS figures. Over the next few months, G2 and Guardian Cities will look behind this statistic to tell the stories of some of those who have died on Britain’s streets. We will tell not just the story of their death, but the story of their life – what they were like as kids, what their dreams were, their hobbies, what people loved about them, what was infuriating. We will also examine what went wrong with their lives, how it impacted on their loved ones, and if anything could have been done differently to prevent their deaths.

As the series develops, we will invite politicians, charities and homelessness organisations to respond to the issues raised. We will also ask readers to offer their own stories and reflections on homelessness. We want the stories we tell to become the fulcrum of a debate about homelessness; to make a difference to a scourge that shames us all.

It is time to stop just passing by.

Was this helpful? Thank you for your feedback.If you look into the background of homeless people, often you find chaos, broken homes, abuse and neglect, but Kenny had a loving family who “never wanted for anything”, Hughes says. She admits that this love could be a bit rough and tumble, though. “We had a running joke in the house. We said: ‘Catherine’s problems came from us.’” She recalls the times when she and her brothers would wrap Kenny in a blanket and tell her they were going to swing her on to the sofa: “So imagine she’s in this cocoon. We used to swing her, but bang her against the wall.” How did she respond? “She’d say: ‘Do it again, do it again!’” Hughes giggles. “And you know turkish delight? Well, she hated turkish delight. So we used to steal all her chocolate out of her selection boxes at Christmas and put all the fucking delights in!” Now she is giggling hard.

Despite Hughes being four years older than her sister, they were close – and always remained so. They were members of the same youth club and played mischievous games together like knock-a-door-run. Catherine, the youngest of four children, was Daddy’s blue-eyed girl. Their father, Michael, worked as a steel fixer, installing the components in construction projects. One day, when Catherine was an infant, he fell 13 metres (42ft) from scaffolding: he fractured his skull, lost an ear and injured his spine. Their mother, also Catherine, was the homemaker before the accident, but afterwards their roles were reversed – Catherine senior worked as a kitchen porter while Michael became the main carer. The younger Catherine became even closer to him.

Hughes says the family always worried for Catherine – there was a “want” in her sister, something missing that she could never put her finger on. This want became more pronounced in her teens after a close friend killed herself. “She suddenly became this rebellious wee kid in the house,” Hughes says. At the same time, she had low self-esteem – she obsessed about her weight, the fact that her left clavicle was smaller than the right, and a small scar across her knuckles (the result of burning herself on a radiator when she was a baby). This tiny blemish stopped Kenny from completing a beauticians’ course. “She would go to massive lengths to look extra-beautiful, because she felt so deep in herself that she was ugly,” Hughes says.

Was she good at school work? Hughes laughs. “No, she was never going to be an academic. She was too crazy for that. She smoked in the school grounds and just caused havoc.” Kenny loved football (Manchester United) and music (Eminem, 50 Cent, Tupac). Her nickname was Moonbeam, “because she was off the planet”, Hughes says. “We used to call her the crazy one.”

Family photos of Catherine Kenny as a child.

The family home was in Downpatrick, a small town in County Down about 20 miles south of Belfast. Although they lived on a predominantly Catholic estate, the children were largely unaffected by the Troubles. “We were sheltered from that, living out of Belfast.” All except Catherine, that is. From a young age, she ran around with the more defiant, politicised kids on the estate and became a staunch nationalist.

“Complex” is the word Hughes returns to repeatedly to describe her sister – gobby, funny, loving, combative, anarchic, oversensitive, self-loathing Catherine Kenny. The family noticed there was a serious problem when she was 16. Her mental health issues became pronounced and she started to drink and take drugs. Despite this, she received no support from local services and deteriorated gradually as she entered adulthood.

Does Hughes think the family could have done more to help? She shakes her head. “Not at all. Back then, there was no talk of mental health issues, and we certainly didn’t know about that. Even in her later years, after she had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, we were never trained to deal with that. We could never have helped her with that. We weren’t professionals.” Hughes believes Kenny’s life could have turned out very differently if she had received wraparound support from a young age.

It was this lack of intervention early in Kenny’s life that led to Hughes butting heads with Joe McCrisken, the coroner at the inquest into her sister’s death. In fact, Hughes says, she was initially opposed to the inquest full stop. “She was dead. I wanted to let it go, let her be at peace,” Hughes says. McCrisken insisted the inquest went ahead. That was when they really clashed. While he acknowledged there were insufficient rehab services, he concluded that Kenny “did receive good care from the health authorities” at various times.

Hughes’s point was that her sister needed the help in her teens, when she first struggled. “I said to him: ‘Joe, with all due respect, I’m not talking about Catherine at the age of 30, I’m talking about Catherine at the age of 14 to 15. That’s when she should have had mental health intervention, that’s when they should have looked after her; not when she was 30.’ Was anyone gonna fix that child by the age of 30?” Right until her death, she referred to Kenny as a child.

Two years on, Hughes is glad McCrisken insisted on the inquest. Unlike many coroners tasked with investigating the death of a homeless person, he treated Kenny with respect and was adamant that lessons would be learned. “To everybody else, she was just a homeless tramp on the street,” Hughes says. “To Joe, she was a human being who should never have died the way she died. He spoke about her with such compassion. He summonsed all the people to court so we could hear for the first time from the first responders at the scene where Catherine died. It was only afterwards that I realised he allowed us to relive her final moments, and we wouldn’t have got that otherwise. He didn’t let her just become a statistic lying dead in a doorway.”

The postmortem examination revealed that Kenny had a blood alcohol level four times the legal limit for driving and had taken the “legal high” MDMB-CHMICA. It was subsequently banned – just a month before the inquest. McCrisken stressed the danger of synthetic cannabinoids, referring to a recent inquest into the death of a 12-year-old who had purchased a “legal high” online, and said that psychoactive substances “pose a very real danger”. It was one of the earliest, and most prophetic, cautions about synthetic cannabinoids. “I can’t emphasise this warning enough,” he said. “I don’t want to be holding another inquest into a death from a legal high, but I fear I will be.”

Nichola Mallon, the deputy leader of the centre-left, nationalist Social Democratic and Labour party and a former lord mayor of Belfast, is sympathetic to Hughes’s view that there should have been an early intervention in Kenny’s case. “It’s not as if people like Catherine are jumping out of the sky and finding themselves homeless on the streets,” she says. “It’s part of a journey, and we should be getting them help early on, rather than leaving them to die in doorways.”

Mallon believes that, since the suspension of Stormont in January 2017, the homelessness problem has grown more acute in Northern Ireland. “We’re failing homeless people and we’re failing them spectacularly,” she says. “Politicians put out statements and we say: ‘This is a tragic loss of life; we must do something about this.’ And then what do we do? We don’t even have a government to hold us to account. Your responsibility as a politician is actually doing something to prevent anybody else from getting into that situation and families suffering that kind of grief again. It’s not good enough to be saying: ‘This is tragic.’”

In her early 20s, Kenny had a son and worked in a bar. “She was a cracking barmaid,” Hughes says, smiling. “She did it for a few years. Everybody loved her.” By 2006, she was still living with her parents, after Hughes and her other siblings had married and moved out. Kenny was drinking heavily – and ferociously. “Catherine was a violent drunk,” Hughes says. “She would start murder down the street. If she was in the pub, she fought like mad; she was a nightmare.”

How do we square the cracking barmaid with the violent drunk? Simple, Hughes says: she was a binge drinker and never drank while working. “The thing you have to understand about Catherine is she could go months on end without a drink, then she’d go off for a week drinking. And you wouldn’t know where she was. Without drink, she was one of the most amazing people you’d have ever met.”

In January 2007, Kenny’s father was diagnosed with lung cancer. He was told the best he could hope for was five more years. Hughes says that Kenny dedicated herself to him for the rest of his life. “My daddy was very, very sick towards the end, and she was so good to him. Oh my God, that child ... what she did for my daddy.” Throughout her life, Kenny showed a desire and ability to look after others while wholly neglecting herself. “Catherine brought in all the strays of the day,” Hughes says. “I swear she brought everything into the house, whether it be dogs, cats, hedgehogs, birds; you name it, she brought it home.”

Their father died aged 62, seven months after his diagnosis. Kenny discovered him in bed after he suffered a rupture in his lungs. “Basically, the tumour dislodged,” Hughes says. “So you can imagine the sight that Catherine found.” Hughes believes that discovering her father like that almost destroyed Kenny. Throughout the three-day wake the family held for him, she was nowhere to be seen. Hughes says Kenny tried to block out her grief with any drugs she could get her hands on.

Despite her worsening condition, Kenny continued to care for her mother, who by now also had a lung disease. She died 17 months later, aged 63, in January 2009. Kenny could not cope in the family home by herself. Hughes and her husband, Darren, secured her a flat close to them on the outskirts of Downpatrick. Despite their best intentions, things went horribly wrong. “Jesus Christ, the heartache that child caused. Between parties, drinking, taking drugs, at this point crystal meth came into the scene. When this hateful drug came on the scene ... That smell – when I think of that word, I can smell that smell.”

“Metallic,” Moore says.

“Yeah, that’s exactly it,” says Hughes, wincing.

We break off for lunch – a platter of ham and cheese sandwiches, mugs of tea and shortcake. Hughes opens up a giant memorial scrapbook that is lying on the desk. Flowers frame a photograph of Kenny on the front cover. The inside has been lovingly curated with childhood photos, more recent snaps, letters and other memories from her life. The scrapbook has become a prized possession for Hughes.

There are photos of young, playful Catherine with her siblings; glamorous Catherine in her 20s, wearing a sheer, white silk top; adoring Catherine with her young son. Hughes passes over the latter quickly, saying she cannot talk about her nephew. We ask when Kenny was at her happiest. Hughes looks upset. She gestures silently to the photos of her sister with her son before moving on.

The scrapbook contains a letter sent to Hughes after Kenny died, from a woman who was a stranger to the rest of the family. Kenny had known the letter-writer’s son, who had killed himself; she had paid her a visit after his death. “I’ve never forgotten Katy’s [Catherine’s] visit,” she wrote. “Katy brought sunshine that day to a grieving mother who could only see darkness. Her act of kindness speaks volumes about the person she was. I feel very privileged and grateful to have known her.” Another instance of the woman who was so hopeless at looking after herself taking care of others.

‘When Catherine died, I was so lost.’ Catherine’s sister, Lee-Maria Hughes. Photograph: Paul McErlane/The Guardian

We come across a poignant card in the scrapbook that Kenny sent to Hughes and her husband in 2012, four years before she died. Revealingly, she refers to her as “mummy”, as well as her sister. “To my sister, best friend in the world and mummy for your amazing strength and patience above all, for standing by me and never giving up on me. I will make you proud of me, I love you with all my heart and soul and for letting me be a part of my wee man Jack’s [Hughes’s son’s] life. And to my big bro [Darren], I’m sorry for being so much hard work and for all the bad I’ve done on you, but I know you will be there to watch me grow and change and be a proper sister to you and your amazing wife and to be a good example of an aunty to Jack.”

But she never did manage to change. At 28, she was finally diagnosed with emotionally unstable personality disorder. She self-harmed frequently and attempted suicide several times. Hughes recalls one frustrating meeting with a community crisis team in 2014: “This guy came into my sister’s house and she’s sliced all over, arms bleeding everywhere, and I remember him sitting down – condescending bastard if I ever met one – and he said to my sister: ‘Tell me this, Catherine, do you drink because you’re depressed or are you depressed because you drink?’ And she says: ‘I’m depressed because I drink.’ Had she answered that the other way, he would have helped her, but he didn’t. He got up and he said: ‘Stop drinking!’ and walked out and left me with that child bleeding from every place on her arms.”

Kenny became homeless a year after that meeting and spent the final year of her life on the streets. Hughes says it was a terrible period for her sister. For the first time, Kenny started to drink constantly. Hughes knows of at least three times that she was viciously attacked while living on the streets. She shows us a distressing photograph of Kenny lying asleep in a hospital bed, her face a grisly patchwork of cuts, bruises, scars and stitches.

It was on the streets that Kenny came into contact with Sandra Moore at the Welcome Organisation. Moore started working for the Welcome 12 years ago. Back then, the organisation was a tiny outfit operating from an old laundry, equipped only with a domestic-sized kitchen to feed 40 to 50 homeless people a day. This was before the UK’s Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government began its austerity programme, and the challenges were very different: “We had six females who we would have deemed entrenched rough sleepers,” Moore says. Today, women are a much bigger part of the homeless picture in Northern Ireland. Out of the 205 homeless people who died in Northern Ireland in the 18 months before March 2019, 80 – almost four in 10 – were women, including a 101-year-old woman and 17 women aged 80 or older. In England and Wales, the latest data from the Office for National Statistics shows that 88% of the estimated 726 homeless people who died in 2018 were men.

Clare Bailey, the leader of Northern Ireland’s Green party, last year described the statistics as “brutally shocking”. But, on the streets, the homelessness crisis seems no worse than in the rest of the UK – and less conspicuous than in English cities such as London, Birmingham and Manchester. There is a simple reason that the figures for homeless deaths in Northern Ireland appear so alarming – the way they are counted.

The Northern Ireland Housing Executive count is based on homelessness applications and includes sofa surfers and people sleeping in temporary accommodation or hostels; the ONS defines people who have died homeless in England and Wales as those whose death certificates state explicitly that they were of no fixed abode, homeless or using homeless hostels and emergency shelters. In other words, the figures produced by the ONS for England and Wales are a measure of the most extreme form of homelessness – street homelessness. This helps to explain why in Northern Ireland women account for a larger proportion of homeless deaths than in England and Wales.

The number of people sleeping rough changes by the day, but it is a tiny proportion of the 320,000 people that the charity Shelter estimated were homeless in Britain in 2018. For example, in autumn 2017, it was estimated that 4,751 people slept rough in England. While Northern Ireland’s figure for homeless deaths is significantly higher proportionally than in England and Wales, its figures for rough sleeping are in fact lower than in many regions of England and Wales.

Moore does not sentimentalise the street homeless people of Belfast. Many are difficult to work with, and Kenny was no exception. “On one occasion, I had picked up Catherine from the streets to take her back to the Welcome. I was bringing her out of the van and she didn’t want to come out ... I was kind of frog-marching her and she was calling me delightful names. ‘Fucking let me lie there. I was comfortable, you fucking bastard.’” Moore smiles at the memory. Even when Kenny gave her “dog’s abuse”, Moore could not help but like her.

The sisters on Lee-Maria’s wedding day

Moore and Hughes believe that the abuse stemmed from Kenny’s feelings of worthlessness. “Catherine’s biggest issue was the fact she didn’t believe she deserved love and help and gratitude and all those compassionate things that people offer,” Hughes says. Moore notes that it is common for the people she helps to resist support: “They challenge, challenge, challenge, because they can’t get their head around the fact that somebody actually cares.”

Kenny was a scrapper, and she enjoyed pitting her slight frame – she was 1.4 metres (4ft 8in) tall and weighed 41kg (6st 7lb) – against an opponent in a different weight division. Often, it affected the family. In 2002, the first year Hughes and Darren were together, he spent Christmas Eve with Kenny at hospital after she got hurt in a drunken brawl in the city centre.

Kenny, a devout Catholic as well as a nationalist, adored Darren, but that did not exempt him from her taunting. “Everybody knew who Catherine was, and you either liked it or lumped it,” Hughes says. “That was her attitude. My husband is a Protestant, and she tortured him.” What did she call him? “Black bastard.” She looks embarrassed. “Black bastard” is a pejorative directed at the unionist community in Northern Ireland, particularly those in the police. Kenny would never shy away from a fight – particularly with the police. In 2011, she was imprisoned for assaulting a police officer.

Four months before she died, she was imprisoned for a second time. Hughes believes a warrant for her arrest, for disorderly behaviour, had been out for months and she was picked up off the street. Kenny served three months in Hydebank Wood College prison. After almost a year of rough sleeping, she was weak and vulnerable, having been the victim of multiple assaults on the streets. How does Hughes feel about the fact that her sister was jailed when she was in such a state? “I was pleased. I know that’s selfish of me, but I knew she was safe and was getting dry and getting all her square meals and getting her medical attention.” Yes, of course, Hughes says she would have preferred her to be in rehab, but prison was the next best option.

Kenny was popular among the homeless community in Belfast and had become especially close to Jimmy Coulter, with whom she often slept rough. While it was reported in the local press that Coulter and Kenny were in a relationship, Moore says it is more accurate to describe the pair as a “couple of bestie mates”. Two days before Kenny was due to be released from prison, Coulter died on the streets of Belfast. Hughes is convinced that the prison’s failure to tell her sister that Coulter had died was a key factor in her eventual death.

“I rang the prison and I said: ‘It’s really important that Catherine is told this news,’” Hughes says. “If she comes out to this news, this is going to send her over the edge. But, in their professional opinion, they thought that would be the biggest mistake ever.” According to Hughes, the prison did not want to risk informing Kenny of her friend’s death, lest it destabilise her. Hydebank Wood College prison declined to comment.

On Kenny’s release, Hughes ensured that she was met at the prison gate by Donna and Jim Connor from Hope Outreach, which works with the Welcome Organisation. They spent most of the day with her, but after she discovered what had happened to Coulter she was angry and wanted to be alone – on the street. “She went off the Richter scale,” Hughes says. “She had been 12 weeks sober and clean and, after receiving the news, she pumped every fucking narcotic that she could get into her body. Oh my God, it was horrendous.”

Did Hughes consider bringing Kenny home with her? No, she says: however much she loved her sister, she could not have done that. “If I had made the decision to bring Catherine here, in the eyes of social services, I would have put my child at risk. Not in my eyes, because I knew Catherine would never, ever have been a threat to my son. He is, ultimately, my main priority. As much as I’d done for Catherine, Jack always came first.

“The second reason I didn’t have her here is that I would never have wanted Jack to witness Catherine like that, and he never did, because in his wee head he had his idea who his aunty Catherine was before it all went terribly wrong for her, and I would never want to taint that memory.”

Hughes describes the final 11 months of Kenny’s life, when she was living on the streets, as “a whole new level of horror”. She says there is a final reason she didn’t invite her into her home. “Catherine had a dual addiction to alcohol and drugs. There was no way I was ever going to keep her in my house unless I’d locked her in a bedroom. She would never have stayed. She simply would never have stayed.”

Kenny had a number of seizures over the following four weeks. On Monday 14 March, she suffered a huge seizure and was hospitalised. The next day, Hughes spent many hours trying to get her into rehab units across Northern Ireland. “I finally get speaking to a girl up in Derry, and I remember it as clear as day. I said: ‘I need you to take my sister, please help me get my sister better,’ and she said to me: ‘The soonest I can see your sister is three weeks. If I deem her fit to come in and use our services, then that is what will happen.’ I said: ‘Well, what would you like me to do with my sister for three weeks?’ She said: ‘I have no idea, but she can’t come here.’ And my sister died four days later in a stinking, dirty doorway in our capital city. Jesus Christ, where is the humanity in that?”

On the Wednesday, Kenny discharged herself from hospital. Three days later, Hughes received a visit from the police in an unmarked squad car. She says she knew in her heart why they were there. “I’ll never forget it until the day I take my last breath. Darren said: ‘This is the knock – it’s going to change your life.’” She opened the door and was greeted by a tall policeman. “He says: ‘There’s no easy way to say this: Catherine was found dead an hour ago.’ And my world came crashing down around me.” It was five weeks since Coulter had been found dead in the same doorway.

Hughes says so many people rang her to offer condolences, but she did not answer. She refused to accept her sister had died until her body had been identified. Darren and her brother David went to the morgue. Kenny still had a cannula in her left hand, which obscured the scar she got from burning her hand as a baby. “David knew it was her, but he wanted to see the scar. He tried to take the bandage off and the policeman had to restrain him. He was like: ‘I need to see the scar, you need to show me the scar.’” Sure enough, he got to see the scar.

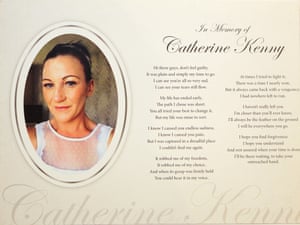

Hundreds of people attended Kenny’s funeral. The service card contains a poem. It is a tender, raw and unblinking account of Kenny’s curtailed life, written in the first person. It was Darren who wrote the poem, on the day he and Hughes discovered she had died. “I don’t think he’d ever written a poem in his life,” Hughes says. “I read it at the service and, honestly, you could have heard a pin drop.” The poem contains the lines:

I’ll always be that feather on your ground,

I’ll be everywhere you go.

Hughes now has a feather tattooed on her back, along with the words: “I’ll be everywhere you go.”

Before her sister’s death, Hughes’s own life was in chaos, but it was a chaos on which she thrived. “When Catherine died, I was so lost,” she says. Hughes had been “at the top of my game”, working as a sales rep in the plumbing and heating industry. After Kenny died, she gave up her job. “I couldn’t function without Catherine. I became an introvert. I didn’t want to deal with anybody outside of my own four walls, and I mean nobody. People wanted to talk about it, people wanted to express their sympathies. But nobody got a piece of me.”

Hughes felt she had lost her sense of purpose. “I battled every day with Catherine and her addictions for 16 years of her life, from when she was 16 till she was 32 and took her last breath. My life was consumed by her. But that was my choice to remain involved, to try to champion her, encourage her, to tell her she was worth more than she believed she was worth.” Hughes is aware there were people who asked why she bothered. But she knows exactly why – because she was her sister, because she had promised their mother on her deathbed that she would look after her, because she loved Catherine.

Three years on, she has started remaking her world. She has got a new job – as a buyer, rather than a salesperson. She has raised thousands of pounds for the Welcome and made it her mission to highlight the homelessness crisis in Northern Ireland – to make sure that her sister did not die for nothing. Finally, she says, she is beginning to come to terms with her death. “I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced the loss of someone, when you get that pain in your heart and that lump in your throat and you can’t take a deep breath. I suffered that for two years – two years solid – before I could actually take a breath.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailing jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found atbefrienders.org

If you are worried about becoming homeless, contact the housing department of your local authority to fill in a homeless application. You can use the gov.uk website to find your local council

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center